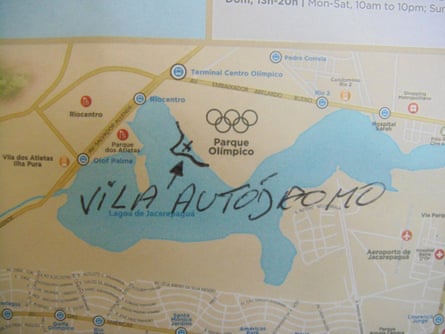

During the Olympic Games the favela of Vila Autódromo attracted as much media attention as any other neighbourhood in Rio De Janeiro, but you won’t find it on the map – not the official one at least.

Despite winning a drawn-out legal battle to save a tiny slice of their community from the bulldozers clearing a path for Olympic and Paralympic Games infrastructure, residents of Vila Autódromo were furious to discover that they had been wiped off the map anyway.

The community’s Facebook group last month posted a photo of the official city guide’s omission of the favela in favour of a solid chunk of beige representing Olympic Park. “Vila Autódromo is here, yes! Counting us out of the maps produced by the City Council is divisive and antisocial,” the post read.

While city authorities might be ignoring poorer parts of the city, private companies such as Google are stepping in to map previously excluded parts of Rio de Janeiro.

Urban planner Raquel Rolnik, former UN special rapporteur on adequate housing, says exclusions from maps have long proved a key element for Rio in securing moral and legal authority for evicting favela residents, with tens of thousands losing their homes in the lead-up to the Olympic Games alone. She says favelas have been fighting for decades just to make it on to the planning maps that serve as the basis for determining provision of city services and on where to stage construction projects.

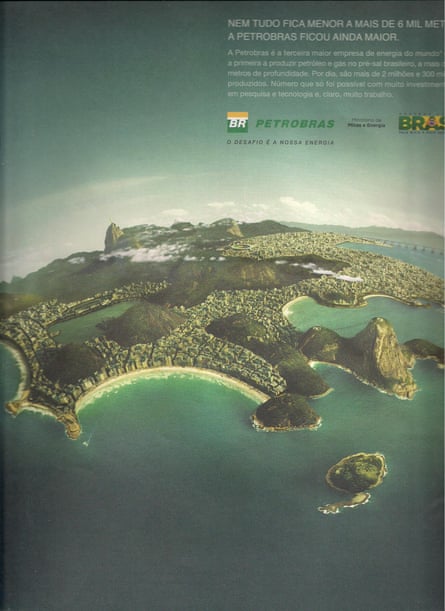

“This Vila Autódromo situation reminds me of a [Brazilian Petroleum giant] Petrobras advertisement that showed the city from above, and if you see the picture it has the landscape of Rio without any favelas in the hills, which are completely green,” Rolnik says. “That’s a powerful mechanism of denial of existence.”

The Rio De Janeiro city council produced the guide through its tourism arm RioTur, which in turn commissioned Mirian Isabel Say of Temática Cartografia to create the map.

“There was no discrimination, prejudice or deliberate exclusion,” Say explains. She argues it is not technically feasible to include all details of a city in a tourist map, and that if residents were unhappy they could provide feedback for consideration in the next update.

Say’s efforts with RioTur certainly went further than previous editions of the agency’s city guides, which like the Petrobras advertisement and the work of many private mapmaking companies render even high-profile favelas like Vidigal, one of the city’s top tourist attractions, and Rocinha, featuring a population of more than 70,000, as uninhabited jungle backdrops for the wealthy urban enclaves of São Conrado and Leblon.

Online map providers once excluded favelas as well, but the digital topography is changing rapidly. Microsoft and Google have both ramped up coverage of Rio’s informal urban areas, however, the inclusion of certain favelas with a high crime rate proved controversial last year when 70-year-old Regina Murmura was murdered after the Google-owned Waze app directed her to a dangerous area featuring a street with the same name as her intended destination. In response Waze introduced an automatic warning system for Rio users when they choose a route through high-crime areas.

Google Maps meanwhile has abandoned its previous approach of showing these communities as blank spaces, taking the opportunity to expand into the city’s untapped market of roughly 1.4 million favela residents.

Unmapped, these residents “have no addresses to list on job applications or bank accounts, and aren’t able to access many economic opportunities, essential services, even basic rights as citizens,” wrote Google director of global product partnerships Alessandro Germano in a post on the company’s blog in July.

The company enlisted, via local NGO AfroReggae, waves of residents equipped with backpack-mounted cameras for coverage of streets too narrow and steep for the company’s Street View cars. Google says it has now mapped 26 favelas.

It also launched an online video tour of Rio’s favelas as part of a bid to humanise the residents of areas many foreign tourists and even Brazilians are too fearful to visit.

Rocinha resident Carlos Pragradar says it is frustrating his favela has been overlooked for so long, but appreciates the inclusion on Google Maps and has made sure the music classes he teaches are marked online.

“The music school is for children but I also do our carnival street band, which could be something for tourists, so hopefully being on the map can help us grow,” he says. “Rocinha has capoeira, it has lots of things – this gives us visibility.”

Google’s most powerful contribution might not even be deliberate. As the photos are only updated periodically, going for a virtual stroll in Street View doesn’t just show the current state of neighbourhoods, but how they once were. That includes Vila Autódromo before and during the evictions that saw most of the former fishing community wiped out.

Where today sprawls the asphalt of an Olympic Park bus interchange, on Street View some of the now-demolished dusty streets of the favela hauntingly linger on, residents frozen in time as they go about their day.

From denying the existence of favelas to providing evidence of what is lost when such communities are destroyed, mapmaking organisations appear to have travelled in a full circle.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion