Want to listen to this article out loud? Hear it on Slate Voice.

When I saw images of white supremacists raging through Charlottesville this past week, I was angered and saddened, but I was not surprised.

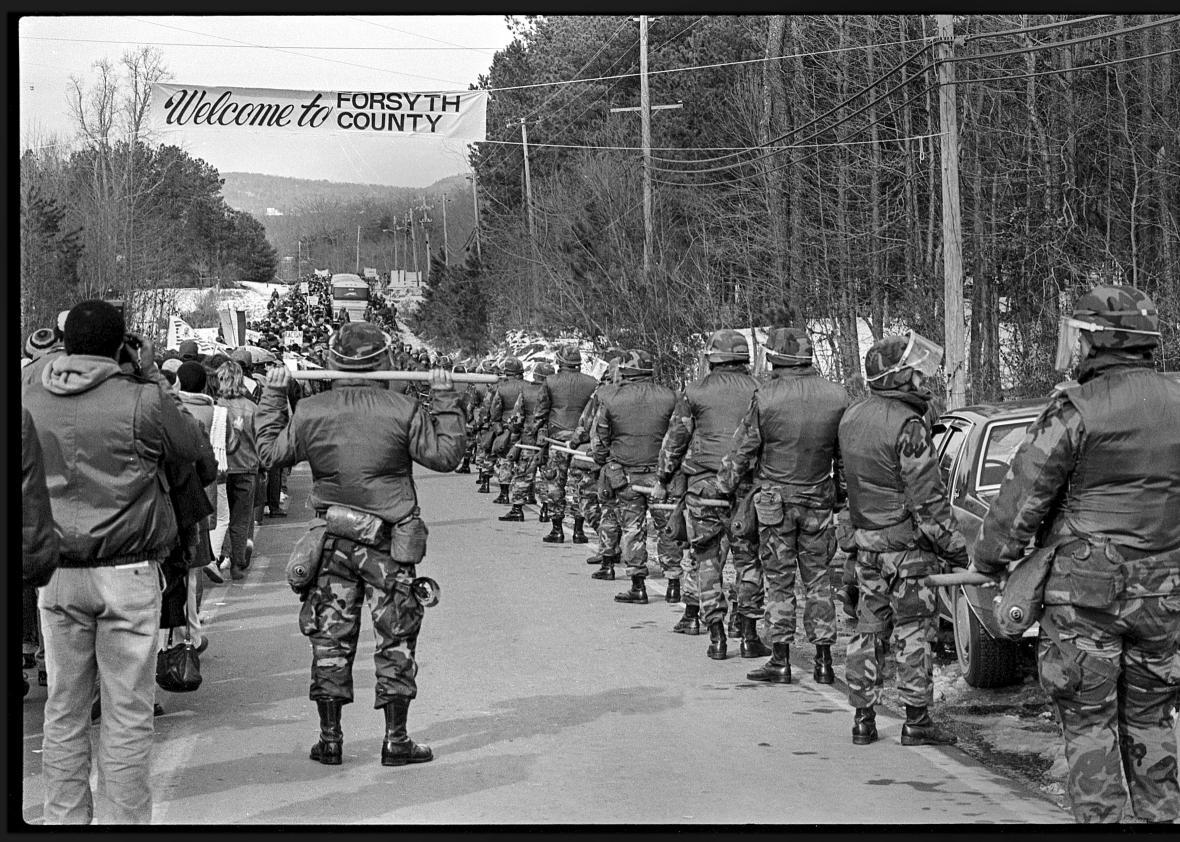

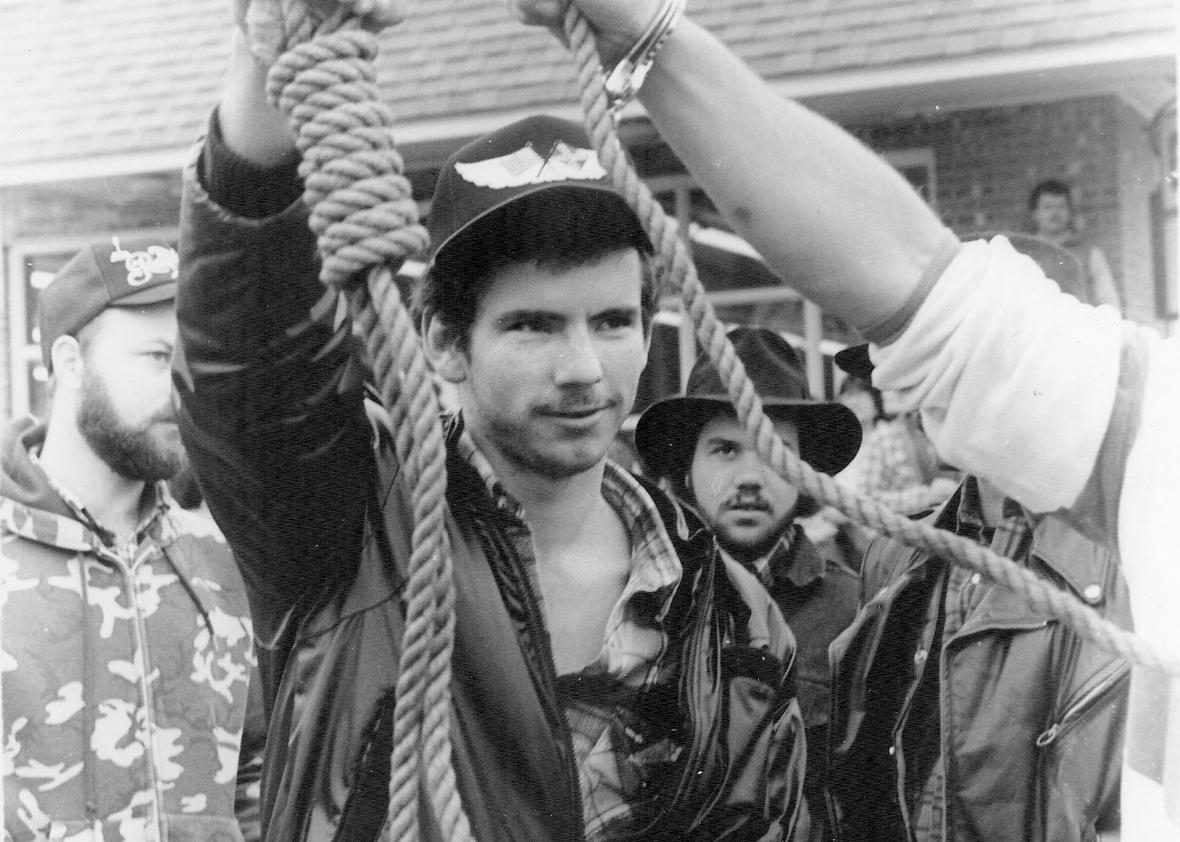

I was raised in Forsyth County, Georgia, one of the most notorious “white counties” in America, and a place where mob violence was the law of the land for nearly a century. After a young woman was murdered there in the fall of 1912, whites lynched a local black man, then waged a months-long campaign of terror that drove out every last black neighbor. For decades after, residents attacked any nonwhite who dared to step over the county line and kept Forsyth all-white throughout my childhood in the 1970s. In 1987, when a group of locals, including my family, marched to protest the ongoing segregation, we were met by an army of white supremacists who vowed to “Keep Forsyth White” and paraded through the streets of my hometown with nooses slung over their shoulders.

Molly Read Woo

This week I have heard many white people express astonishment that such racial hatred is still part of American life. Michael Eric Dyson rightly calls such naïveté our “fatal forgetfulness.” For there is nothing new about what happened in Charlottesville, and we don’t have to look back more than a few years to find other examples of white terrorists killing innocent people: from James Harris Jackson’s 2017 stabbing of Timothy Caughman on a street in Manhattan; to Dylann Roof’s massacre of nine parishioners at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015; to Wade Michael Page’s 2012 shooting spree at the Sikh Temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin.

While the list of such attacks grows longer every year, with Heather Heyer’s name now added, many white moderates cling to the fantasy that the next generation will inevitably be less racist. But growing up in the apartheid world of Forsyth County taught me that racism is not a mysterious fever that simply passes with time. It is a culture that is learned, and passed down. I watched that process all through my childhood, as kids at my elementary school told more and more racist jokes every year, and gradually hardened, right before my eyes, into the vicious bigotry of their parents and grandparents. By the time we were teenagers, I recognized some of my old classmates in the mob of locals who threw rocks and bottles at peaceful marchers in 1987.

In the wake of Charlottesville, our national battles lines are drawn just as clearly as they were that day in Forsyth, when civil rights leader Hosea Williams stood on one side of a country road singing “We Shall Overcome,” and on the other side seething whites chanted, “Go Home Nigger! Go Home Nigger!”

Now, as then, it is not the actions of violent mob members that will tip the scales but the choices of those tempted to remain quiet. The whites-only rule lasted for decades in Forsyth County not because groups of white men committed acts of violence, but because thousands of their friends, relatives, neighbors, and co-workers upheld a code of silence. By refusing to publicly condemn bigotry that, privately, they did not condone, even peaceful Forsyth residents were complicit in the crime. For years, our silence was interpreted as consent.

A decade ago, I finally woke from my own “fatal forgetfulness” and began researching the buried history of the racial cleansing that transformed Forsyth in 1912 and cast a century-long shadow of hate. And that, ultimately, is what the Charlottesville debate is about: whether good and decent white Americans are willing to give up our innocence, break our habit of silent complicity with racial injustice, and finally face our black brothers and sisters with honesty, empathy, and compassion. Removing monuments to the men who enslaved their ancestors is, truly, the very least we can do. It is not the end of our long-deferred process of truth and reconciliation, but a way to finally begin.