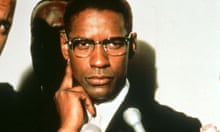

Of all the American leaders who were assassinated in the 60s, that decade of turmoil and revolt, Malcolm X has enjoyed the greatest upturn in posthumous fortune. In the pantheon of black American protest figures only Martin Luther King occupies a more exalted position, but it is Malcolm X whose legend has the greater street credibility and aura of cool. It's he who was the subject of Spike Lee's biopic starring Denzel Washington, and it is Malcolm, not Martin, who today is cited by radicals and rap stars.

Yet Malcolm Little, as he was born, was a petty thief and a pimp who found salvation in the Nation of Islam (NOI), a bizarre cult led by a mountebank and sexual predator named Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad preached that white people were a race of devils created 6,000 years ago by an evil scientist named Yakub. As Muhammad's leading minister, Malcolm X rejected the civil rights movement, labelled Dr King a "house Negro", and formed liaisons with the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi party – organisations that he found preferable to mainstream political parties.

Although the Nation of Islam continually boasted of its willingness to defend itself and by extension the black community, it reserved its fire power for its own members, severely beating anyone who stepped out of line, and killing those (like Malcolm himself) who were deemed a threat to Muhammad. Malcolm X knew this, but he stayed loyal to the cause for the better part of his adulthood – only breaking from the NOI in his last year of life, when he was kicked out in an internal power play.

How and why has death treated him so well? One reason is the Autobiography of Malcolm X, a memoir ghosted by Alex Haley, who later wrote the Afro-American blockbuster Roots. The autobiography sold more than 6 million copies in the 10 years following Malcolm's murder by NOI hitmen in 1965, and continues to be a key revolutionary text. A gripping mixture of urban confessional and political manifesto, it not only inspired a generation of black activists, but drove home the bitter realities of racism to a mainstream white liberal audience.

But if the book's success established Malcolm's legacy, it also created a myth that deterred a more stringent analysis of his life and work. Now, almost a half century on, Malcolm has finally received the biography that his unique role in black and global resistance culture demands.

Manning Marable, who died on 1 April after a long illness, was professor of history and political science at Columbia University and was steeped in African-American studies. He has left a meticulous, comprehensive and fair-minded portrait of both Malcolm and the turbulent period of American history in which he lived and died. We learn that the "Detroit Red" image of Malcolm as a street hoodlum was exaggerated in the autobiography, the better to dramatise his conversion to the law-abiding but society-rejecting doctrine of Muhammad's NOI.

Long before multiculturalism entered the language of political discourse, Malcolm was busy exploring its logical endpoint of ethnic and cultural separation – which helps explain his collusion with far-right white racists, including meetings with the Ku Klux Klan and verbal support for Nazis. But then Malcolm said many things. As Manning shows, he was adept at tailoring his message to different audiences, often blatantly contradicting on a Wednesday what he had clearly and emotively stated on a Monday.

Not the least of Malcolm's flaws was his attitude to women, and his wife in particular. Betty Shabazz was abandoned in her home for the greater part of her marriage, including the period during which Malcolm and his family were targets of a campaign of NOI intimidation. Malcolm's habit, after the birth of each of his four children, was to embark on distant speaking tours.

Yet despite all of this, the man who emerges from this book is in many respects admirable: brave, loyal, self-disciplined, quick-witted, charismatic, acutely intelligent and a public speaker of quite awesome power. A fallacy that has grown over the years is that there were three distinct Malcolms: the street thug, the white-hating demagogue and, after his split with the NOI, a liberal integrationist who was in essence a slightly more outspoken Dr King.

Regardless of his book's subtitle, Manning convincingly argues that there was in fact a much stronger continuum. Malcolm (whose father was probably murdered by white racists) was first of all the child of supporters of the black nationalist Marcus Garvey. And while he softened his position vis-a-vis white America in his post-NOI phase, he remained capable of vehement anti-white rhetoric and overwhelmingly concerned with black power.

Given his difficult childhood (he was taken into care and fostered), and the fierce racism that dominated American civil and political life at the time, his attitudes were not surprising. What was out of the ordinary was the unrelenting determination that Malcolm brought to the business of galvanising black America. Lacking a formal education, he became a voracious reader and an inspired debater. Manning suggests that Malcolm's youthful appreciation of jazz helped create a vocal rhythm that broke from convention and propelled his speeches with a kind of bebop daring.

While Malcolm correctly predicted that black culture would assume a central role in American life, he would never have foreseen the election of a black president. And as is true of many militants, there was no tyrant, however murderous, that he wouldn't praise in the name of anti-imperialism. Yet in truth, he outgrew the NOI strategically and intellectually some years before the final breach, and stayed within the organisation, parroting lines for which he felt increasing contempt, out of blind allegiance. Perhaps he knew that to leave was to sign his death warrant.

In the NOI's newspaper, a few weeks before Malcolm's murder, one of the group's leading ministers declared: "Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death." They were the words of Louis X, who had been Malcolm's most promising disciple. He is now better-known as Louis Farrakhan, the current and long-standing head of the NOI.

Malcolm's killing on 21 February 1965 in front of a Harlem audience that included his wife and young children has been the subject of sometimes deluded speculation. He was shot down by three men, one of whom, a NOI member, was caught and disarmed by the crowd. The two others – whose identities have long been known – escaped, and two entirely innocent men were found guilty and imprisoned in an appalling miscarriage of justice that, ironically, served only to confirm Malcolm's opinion of America's prejudiced legal system.

Manning presents a strong case that there was some form of FBI collusion in the murder, if only to the degree that the bureau, which had spies all over the NoI, failed to prevent the plot. He also floats the probability that at least one of the killers was an FBI informant.

Whatever the truth, there is no disputing that Malcolm was shot dead by men who largely shared his beliefs. Nor that 30 years after his murder more than half a million black men would converge on Washington DC to protest, in the language he made popular, the demonisation and criminalisation of African-American males. The keynote speaker at that "million man march" was Louis Farrakhan. Malcolm, no doubt, would have appreciated history's gift for farce.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion