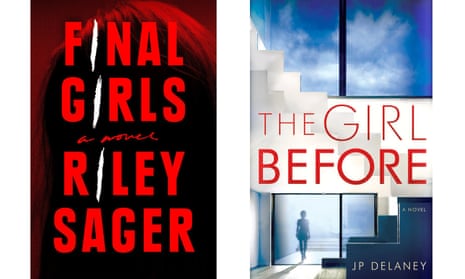

Riley Sager is a debut author whose book, Final Girls, has received the ultimate endorsement. “If you liked Gone Girl, you’ll love this,” Stephen King has said. But unlike Gone Girl, Girl on a Train, The Girls, Luckiest Girl Alive and others, Final Girls is written by a man – Todd Ritter. This detail is missing from Riley Sager’s website which, as the Wall Street Journal has pointed out, refers to the author only by name and without any gender-disclosing pronouns or photographs. (His Twitter avatar is Jamie Lee Curtis.)

Ritter is not the first man to deploy a gender-neutral pen name. JP Delaney (real name Tony Strong) is author of The Girl Before, SK Tremayne (Sean Thomas) wrote The Ice Twins and next year, The Woman in the Window by AJ Finn (AKA Daniel Mallory) is published. Before all of these was SJ (AKA Steve) Watson, the author of 2011’s Before I Go to Sleep.

“Literally, every time I appear in print or public,” Watson says, someone asks about why he uses initials. It was his publisher’s decision to avoid an author photo and to render his biography non-gendered. He has never hidden, but when Before I Go to Sleep went on submission, editors emailed his agent and asked, “What is she like?” Watson found the mistake flattering. Withholding his full identity was a way “to reassure myself that the voice worked”, he says. In the world of romance novels, male authors have long disguised their gender. The Glaswegian author Iain Blair wrote 29 romances as Emma Blair. Jessica Blair is really Bill Spence, Alison Yorke is Christopher Nicole and Dean Koontz has written as Deanna Dwyer. As an undergraduate, Philip Larkin wrote erotic novellas under the name Brunette Coleman.

Others have used a female pen name to escape an identity – such as L Frank Baum, the author of the Wizard of Oz series, who used pseudonyms in the way that JK Rowling became Robert Galbraith to escape Harry Potter. Or Mohammed Moulessehoul, who wrote under his wife’s name, Yasmina Khadra; his books were celebrated as the “authentic voice of the Arab woman” until his real identity was discovered in 2005.

The recent spate of men writing with gender-neutral names seems commercially driven. It is not a necessity for acceptance, as the Brontë sisters or George Eliot felt their pen names to be. However, there are earlier examples of men who wrote as women to give voice to “female” issues at a time when recourse to the females themselves proved elusive or unthinkable. In 1747, Benjamin Franklin published “The Speech of Miss Polly Baker”, and essayist Samuel Johnson presented himself as “Misella”, a sex worker, in 1751.

The work of gender-disguising authors sits within the debate around fiction writing and cultural appropriation (see Lionel Shriver delivering a speech in a sombrero to make the point that writers of fiction must wear other people’s hats). If it is acceptable to disguise or, worse, misrepresent gender in an author’s name, then why not heritage, religion, ethnicity or origins? The poet Michael Derrick Hudson submitted poems under the name Yi-Fen Chou. The line is hard to draw when a writer adapts their name in order to draw closer to a readership. In a world where authenticity is prized, maybe the last fiction readers want to buy is the one about the author’s identity.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion