China’s private companies are the engines of its economy, generating seven-tenths of its GDP and employing 85% of its workforce. As such, the country’s long-term growth hinges on their success. But they’re coming up against a formidable opponent: their own government.

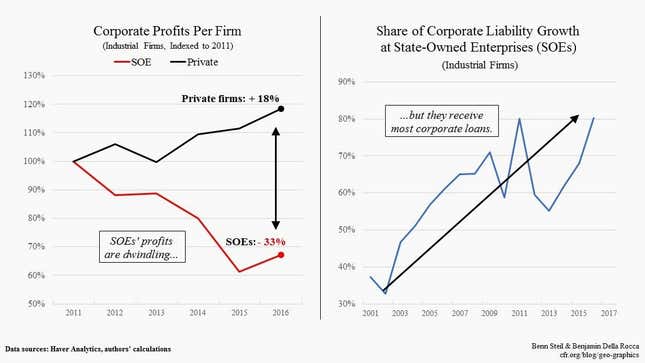

As its economy slows, China’s private companies increasingly find themselves pitted against state-owned firms in the scramble for scarcer resources. One such resource is financing. Thanks to their official imprimatur, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have long enjoyed easier access to credit than private companies. In 2016, industrial SOEs accounted for 80% of growth in corporate debt, compared with just under 60% in 2013, according to the Council on Foreign Relations’ Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca. That would be fine if SOEs were more profitable than private firms. But while private-sector profits rose 18% between 2011 and 2016, those at SOEs sunk 33%, according to Steil and Della Rocca.

In the last two years, as lending has tightened up somewhat, an even more destructive problem has emerged. State firms have been forcing their private suppliers to accept excessively drawn-out payment terms—in effect, sponging free loans off the private sector, says Thomas Gatley, analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, a research firm.

“The result is that private companies are forced to carry a fat cushion of working capital,” or money used to fund day-to-day operations, writes Gatley in a recent note. Meanwhile, SOEs “in aggregate enjoy the luxury of negative working capital,” which liberates them to make more investments.

In his analysis of 338,00 firms, Gatley uncovered a disquieting pattern. Private companies were, unsurprisingly, more profitable, earning a 31% return on capital in 2016, compared with the 9.5% of their SOE peers.

However, private firms socked away seven percentage points of that profit—more than a fifth—into working capital reserves, while SOEs wound up earning a net return on capital of 11%.

Rather than using profits to build new factories and upgrade equipment, private companies are hoarding so much of their earnings that by the end of 2016, private industrial firms alone had stashed away 6.5 trillion yuan ($1 trillion) as working capital reserves, equal to around a fifth of China’s total investment in physical assets that year. Private investment has plunged.

SOEs, flush with free loans from their suppliers, are investing. The worrying thing is in what, exactly—and therein lies one huge problem for China’s long-term growth.

Freed from the pressure to profit, and tasked with being agents of GDP-juicing policy, state firms invest disproportionately in infrastructure. For instance, in 2016, only 9% of SOEs’ fixed-asset investment went toward manufacturing, compared with 65% into infrastructure.

But infrastructure doesn’t generate anywhere near the kind of return that new industrial capacity might. This means “too much capital is being drained out of industry to fund investments in infrastructure that deliver an even lower return,” says Gatley. He notes that the government prefers the “forced transfer of capital” from private companies because it lets SOEs invest without racking up more bank debt, in line with the government’s current campaign against financial risk.

The risks posed by China’s corporate debt are certainly concerning. At around 150% of China’s GDP, its corporate debt levels are among the highest in the world. But the biggest problem for the economy isn’t the risk of corporate default due to high debt, notes Gene Ma, economist at the Institute of International Finance, in a recent analysis (paywall). Rather, it’s the low and shrinking return on corporate assets.

Over the last decade or so, capital has flowed into projects that generate less value than they cost to build. As the share of the economy made up of underperforming projects grows—and with it, the wealth destroyed in those investments—it takes ever-rising sums of new capital to generate the same amount of GDP.

The Chinese government at least seems aware that private investment is collapsing. In Sep. 2017, it released a policy guidance inviting private companies to invest in strategic sectors—big data and robotics, for example—and initiatives like Made in China 2025 that state firms previously dominated, as IIF’s Ma points out (paywall).

But rejigging the incentives that encourage and fund wasteful spending—and, thereby, discourage productive investment—isn’t on the docket. In fact, at the all-important Party conclave in Oct. 2017, Xi called for making SOEs “stronger, better, and bigger.” It’s a formula for leaving the Chinese economy weaker, worse, and ultimately—though probably only in the distant future—smaller.