- India

- International

B R Barwale, 1931 – 2017: The engine oil dealer who fathered India’s seed industry

Today, the estimated annual turnover of the Indian private seed industry is around Rs 13,000 crore, coming mainly from cotton (Rs 4,000 crore), vegetables (Rs 3,000 crore) and maize (Rs 1,500).

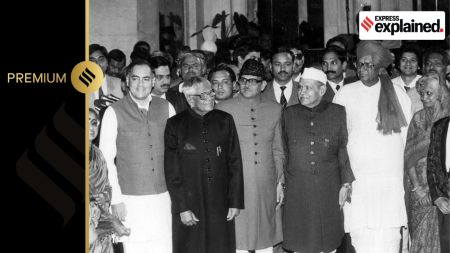

BR Barwale (centre) with the then agriculture minister of Maharashtra

BR Barwale (centre) with the then agriculture minister of MaharashtraSharad Pawar (right) at a Mahyco sorghum trial field in Jalna sometime in the mid-seventies. (photo courtesy:Mahyco)

Sometime around 1959, Badrinarayan Ramulal Barwale ventured into farming of his ancestral land in Mandwa, about 10 km from Jalna town in the Marathwada region of what was soon to be Maharashtra. The 28-year-old class X-pass, who had a Castrol and Burmah-Shell engine oil agency business at Jalna that was mainly a cotton ginning and produce trading centre, began by cultivating Pusa Makhmali, a bhindi (okra or lady’s finger) variety developed by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in New Delhi.

Curiosity to know more took Barwale to an agricultural exhibition organised by the Bharat Krishak Samaj in Delhi. There, he learnt about a new IARI variety Pusa Sawani, which was high-yielding as well as resistant to the yellow vein mosaic virus disease that led to the infected plants bearing small, deformed and yellowish-green fruits. Returning to Jalna with about 2 kg of seeds, Barwale sowed these and invited Harbhajan Singh — the breeder of the variety — to see the developing lush green bhindis on his plot. An impressed Singh told him not to sell the lady’s fingers, but allow the fruits to ripen sufficiently and collect the seeds for sale. That advice is what triggered the transformation of an engine oil dealer who came from a traditional Marwari family of cloth merchants and moneylenders — he had also taken active part in the 1948 movement to integrate the Nizam’s Hyderabad State (of which Marathwada was part) with the Indian Union — into a seed entrepreneur.

Barwale started off by packing and selling Pusa Sawani okra seeds under his own ‘Safal’ brand. The real break, however, came in 1963-64, when the Rockefeller Foundation and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research — which were working towards developing commercial hybrids in maize (corn), jowar (sorghum) and bajra (pearl millet) — identified Barwale as a seed production and multiplication partner. They supplied the genetically pure nucleus seeds of the male and female parental lines. He, then, crossed them for producing the breeder and foundation seeds, which were further multiplied for planting in farmers’ fields.

In November 1964, Barwale incorporated the Maharashtra Hybrids Seeds Company Ltd or Mahyco. It basically undertook commercial seed production and marketing of publicly-bred hybrids — starting with Ganga Safed-2 maize (released in 1963), CSH-1 sorghum (1964) and HB-1 pearl millet (1965), followed by H-4 or Sankar-4 (1970), the world’s first ever cotton hybrid developed by the legendary Chandrakant T Patel — under the Mahyco brand. The company did similar commercialisation with other popular public sector hybrids such as CSH-5 (1975) and CSH-6 (1977) sorghum, and BJ-104 pearl millet (1978).

Towards the early seventies, Mahyco had initiated its own breeding programme. In 1981, MBH-110 pearl millet — which out-yielded BJ-104 and was also less susceptible to the downy mildew fungus — became the first privately-bred hybrid of any crop to be officially released by the Government of India. This, along with MSH-51 (Mahyco Sorghum Hybrid) in 1982 and MECH-1 (Mahyco Early Cotton Hybrid) in 1985, were planted widely in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat. Well before this, Barwale’s son Raju had joined the business, after completing a BSc in agriculture and animal husbandry from Pantnagar University in 1976. His daughter Usha Zehr — a PhD in agronomy from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign — was to also join in 1996, after having worked as geneticist specialising in sorghum and millet at Purdue University.

The next big leap was to happen in the nineties. In late-1990, the architect of India’s Green Revolution M S Swaminathan invited Barwale and Raju to a conference that his foundation was organising in Chennai. Among those who were supposed to attend were scientists from Monsanto; Swaminathan was apparently keen that the Barwales meet them. But that was during the time of the Gulf War and the travel advisories issued by the US government meant the meeting couldn’t take place then.

The two sides did meet, though, a couple of years later in October 1993. Monsanto was at that point working on ‘Bollgard’, a technology for introducing genes from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a soil bacterium, into cotton for imparting resistance to the dreaded American bollworm insect pest. The US life sciences giant was looking for a partner to bring this technology to India. It naturally chose Mahyco, which had already invested nearly Rs 2 crore in setting up a tissue culture and biotechnology lab at Bangalore in 1991.

In October 1997, a 50:50 joint venture Mahyco Monsanto Biotech was formed as the Indian licensor for Bollgard; seed firms could use this recombinant DNA technology to incorporate Bt genes into their cotton hybrids. Within a year, Monsanto also picked up a 26 per cent stake in Mahyco. By 2001, all the biosafety studies and regulatory trials were completed, paving the way for commercial planting. From hardly 0.3 lakh hectares (lh) in 2002, the area under Bt hybrids rose to over 119 lh or 93 per cent of the country’s total cotton acreage in 2014. Over this period, cotton output almost trebled and India surpassed China to emerge as the world’s No. 1 producer.

Today, the estimated annual turnover of the Indian private seed industry is around Rs 13,000 crore, coming mainly from cotton (Rs 4,000 crore), vegetables (Rs 3,000 crore) and maize (Rs 1,500). In crops where hybrid seed adoption rates are high — cotton (95 per cent), sorghum and pearl millet (90 per cent), vegetables (80 per cent) and maize (60-70 per cent) — the private sector has an overwhelming presence. The likes of IARI and other government research institutions retain their dominance largely in rice, wheat, oilseeds and pulses, where hybridisation levels are low.

The man who showed the way here — creating an industry that was practically non-existent till the early sixties — was Badrinarayan Ramulal Barwale.

May 17: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05