In the aftermath of the Las Vegas shooting that killed a staggering 58 people and injured roughly 500 others, the Trump administration has tried to steer Americans away from political debate. “There’s a time and place for political debate, but now is the time to unite as a country,” White House press secretary Sarah Sanders said in a press briefing following the tragedy.

But while it is important to collectively mourn those lost to senseless violence, it is equally important to understand that mass shootings are not isolated events in American society. Mass shootings are still relatively rare in the US, but occur much more often here than in other countries. There are far too many to consider them random, unpreventable acts of violence committed by a deranged individual.

A great deal of commentary attempts to tie mass shootings to a single issue. Often, that seems like the easiest way to make sense of atrocities. That’s why we get sound bites that lean on mental health (when shooters are white), terrorist ties and affiliations (when shooters are brown), gang violence and “urban decay” (when shooters are black), bullying (when it happens in a school), and overwork (when it happens in a workplace).

The truth cannot be boiled down to any single issue. As sociologists, we can look to the bigger picture, point out patterns, and identify common denominators. Our research suggests that gun control is, indeed, an important piece of the problem. But in order to understand the factors behind America’s mass shootings, it is also critical to consider the relationship between masculinity and violence.

International gun ownership and mass shootings

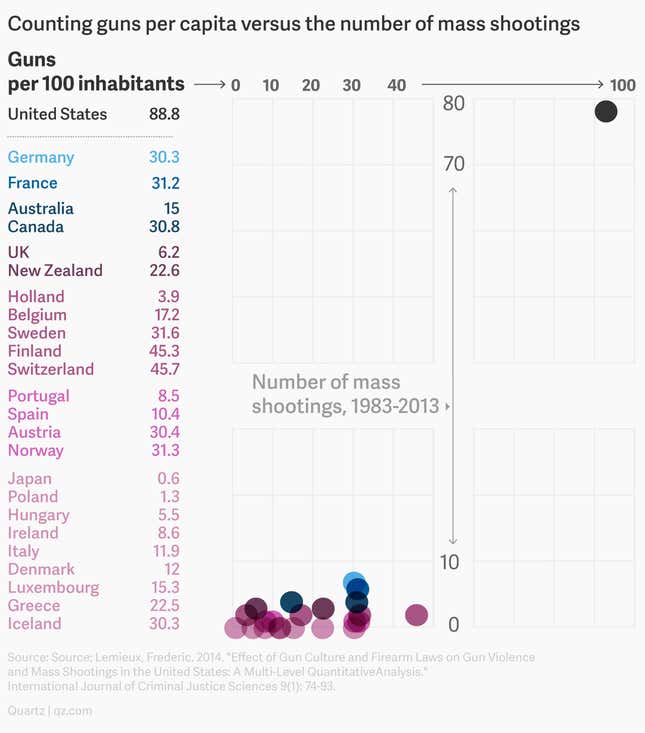

International evidence now makes us incredibly confident when we say that the number of guns in a society is positively correlated with the number of mass shootings in a society, as supported by a study spanning three decades of analysis in a collection of nations around the world.

Look at the clusters of data points. Each represents a different country. The more guns there are in a given country, the more mass shootings it has. But there are two other things worth noticing. For instance, just consider the number of nations in this sample that have approximately 30 guns per 100 people: Austria (30.4), Canada (30.8), France (31.2), Germany (30.3), Iceland (30.3), Norway (31.3), and Sweden (31.6). They don’t all have the same rate of mass shootings over the period of 30 years. Iceland had zero; Norway had one; and Sweden had two. But France had six, and Germany had seven. These are small numbers, but even here, the range is large enough to suggest that the number of guns is not the only factor influencing mass shootings.

It’s also worth highlighting just how much of an outlier the US is when put in international perspective. Sure, we have roughly twice as many guns as the other societies with high numbers of guns owned per inhabitant. But the number of mass shootings the US has experienced makes us an extreme outlier in these data.

The masculinity problem

Scholars who study masculinity and mass shootings have consistently drawn attention to the fact that mass shootings are not only a uniquely American social problem; they are a problem with American men. We’ve argued before that there are two questions that require explanation related to gender and mass shootings. First, why is it that men commit virtually all mass shootings? And second, why do American men commit mass shootings more than men anywhere else in the world?

Why is it men who commit mass shootings?

Social psychologists have a theory referred as “social identity threat” that has been studied across a wide range of contexts. The idea is pretty simple. Research demonstrates that if people feel that a part of their identity that they hold dear is being called into question, they are likely to respond with an exaggerated display of qualities associated with that identity.

Applied to gender, social scientists refer to this issue as “masculinity threat.” Men who have their masculinity called into question (or “threatened” to use the social psychological language) react in patterned ways. Research shows that they are more supportive of violence, less likely to accurately identify sexual coercion as such, and more likely to support statements about the inherent superiority of males, among other responses.

Research has also shown that men whose masculinity has been threatened are more likely to identify as Republican, supported sexually prejudiced statements about gay men, and more supportive of war as a solution to national disputes. They were even more likely to say that they wanted to purchase as SUV. When men’s masculinity is threatened, they don’t respond by backing down; they double down on masculinity and “overcompensate” to demonstrate just how manly they are.

The list of things that men turn to when they feel emasculated is quite revealing about what it means to be masculine in our society. Masculinity is associated with homophobia, sexism, misogyny, male supremacist ideals, and violence, and so men turn to those things in order to demonstrate their membership in the group.

Mass shootings follow a consistent pattern: The men who commit them have often experienced what they perceive as masculinity threats. They’re bullied by peers, gay-baited by classmates, and often perceive themselves as unable to live up to societal expectations associated with masculinity, such holding down a steady job, having sexual access to women’s bodies, or being tough or strong.

This does not suggest that men are somehow inherently, unavoidably more violent than women. But it does suggest that mass shootings need to be seen, in part, as enactments of masculinity.

Why do American men commit mass shootings more than men elsewhere?

Certainly men have their masculinity threatened in other societies as well. So why is it that American boys and men are so much more likely to respond to threats with such extreme forms of mass violence?

The answer is that American culture plays a role in supporting this kind of violence. Consider the sociocultural contexts in which these kinds of violent masculinities are produced and (sometimes) valorized. Men have been the beneficiaries of an extraordinary amount of privilege over the course of human history—white, heterosexual, able-bodied, educated, class-privileged, American men in particular. Now a great deal of progress has been made toward chipping some of that privilege away or, at the very least, publicly calling it into question. Gender inequality is alive and well today, but it is also true that men—as a group—have witnessed the gradual erosion of privileges previous generations of men took for granted. Sociologist Michael Kimmel suggests that this shift has produced a uniquely American sentiment among men that he refers to as “aggrieved entitlement.”

Many men still feel entitled to the forms of privilege their fathers, grandfathers, and great grandfathers cashed in on. And they are resentful of the fact that what they feel to be rightfully theirs feels like its slipping away. Neither we nor Kimmel are suggesting that feeling pissed off about these changes will always lead to mass shootings. Rather, mass shootings are simply an extremely violent example of a more general issue regarding shifts in relations between women and men and historical transformations in systems of social inequality.

What’s next?

When asked to suggest a motive for the attack in Las Vegas, sheriff Joe Lombardo replied, “I can’t get into the mind of a psychopath at this point.” Similarly, a wide variety of statements from public officials and beyond are pointing to severe mental illness as the cause. During these moments, however, it is important to recognize that these statements contrasts sharply with statements from family and friends—those who knew him best. The general manager of one of the gun stores from which the shooter purchased weapons justified his sale of the weapons by describing the shooter as “a normal fellow, a normal guy – nothing out of the ordinary.” His neighbor concurred, describing him as “a normal man.” His brother said something similar.

The scary realization that research and data support is that, in the US, “normal guys” sometimes commit mass shootings. As sociologist Kieran Healy put it, mass shootings are “by now well institutionalized as a mode of violence. When one happens, everybody knows what to do.” There’s a script mass shootings follow; they are socially patterned actions. And they are gendered patterns of action as well, which means that men who want to find a way to assert their masculinity have a clear path to turn to.

Combine these gendered factors with a society in which guns are extremely available and highly valorized in popular culture and the media, and mass shootings will continue to be an American problem. Research suggests that solving this problem requires us thinking about it from multiple angles, recognizing that each can only offer a partial solution.

Certainly, gun control is a vital aspect of any solution to mass shootings in the US. But real change requires a cultural solution as well, one that attempts to invest in new ideals associated with masculinity not founded on dominance, violence, and ideologies of male supremacy. Mass shootings will continue to occur as long as we ignore these connections, and as long as we fail to recognize that mass shootings in American society are deeply entwined with our culture and politics.