Flaws threaten Hong Kong air safety, claim aviation experts

After a series of near misses, Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department is criticised for inadequate staffing and a failure to follow incident-reporting guidelines

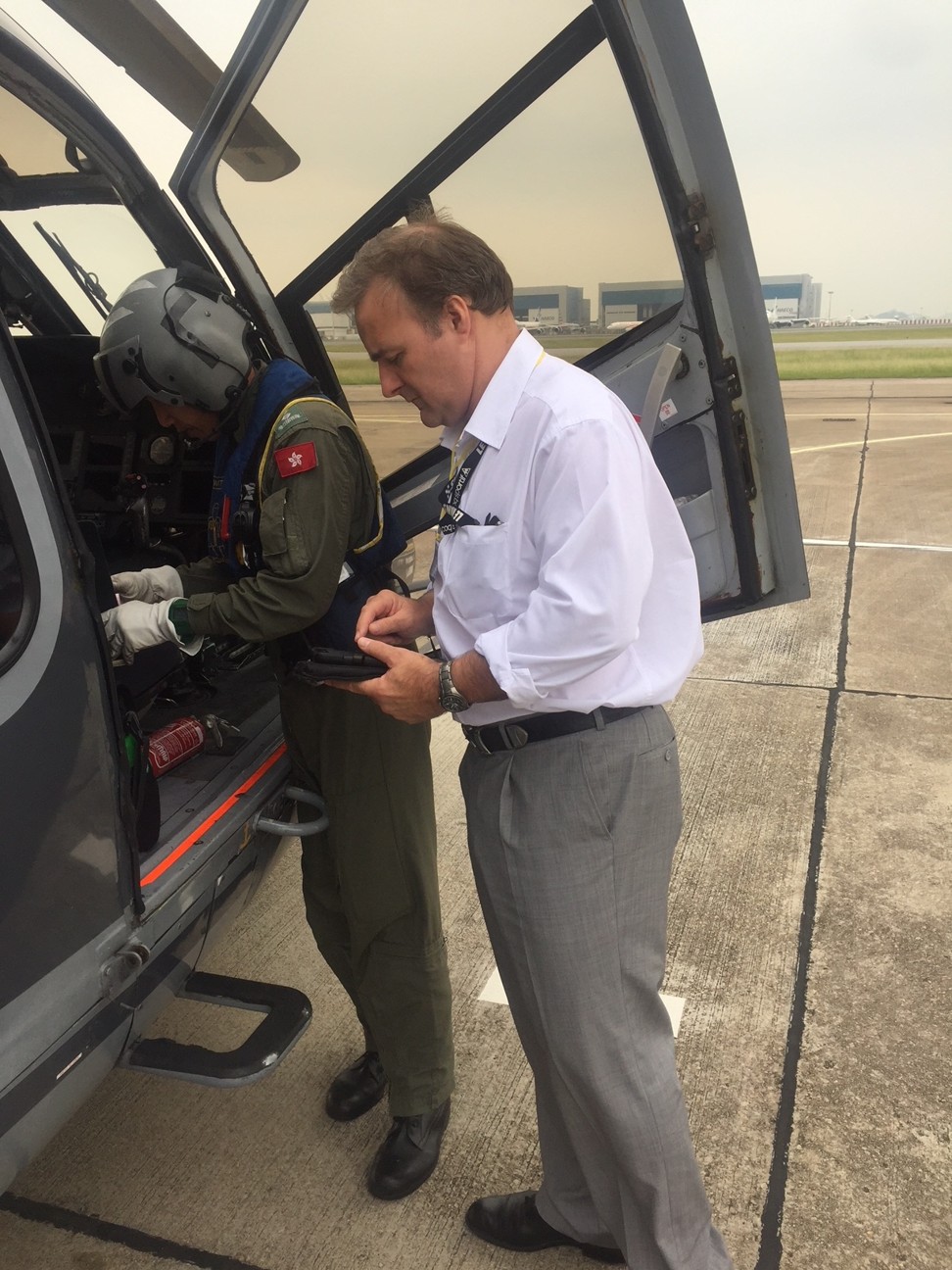

“They had ground proximity warnings activating in the aircraft. Apart from a crash, you cannot get much more serious an incident,” says experienced pilot and former Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department (CAD) flight operations inspector Damian Roberts.

Other pilots interviewed for this article support Roberts’ allegations, and suggest the CAD has too few inspectors and that those it does employ are not qualified to do the job adequately.

With regards to flight safety, it’s like talking to a brick wall, the Civil Aviation Department is not fit for purpose

Before he leaves, however, he wants to expose what he regards as dangerous failings in Hong Kong’s aviation set up. “Safety is dependent on an open reporting culture [so lessons can be learned], but my experience was that this was not the case at HKCAD,” he says.

For example, “In a helicopter there are international guidelines for a mandatory occurrence report (MOR) to be submitted within 96 hours of an incident,” Roberts says. “That’s the law.” Instead, he claims, the Government Flying Service (GFS), which operates medical emergency and search and rescue services, fails to submit MORs. Roberts shows me apparent evidence (stills from a video appearing to show the tail rotor of a GFS helicopter striking an overhead cable) and email correspondence between him and his superiors about two instances in which the GFS did not submit MORs, one in March of this year, the other in August.

“GFS are a law unto themselves and hold the CAD in complete contempt,” Roberts says, adding that

if things are alarming in helicopter safety regulation, former colleagues concerned with fixed-wing aviation safety have told him the situation is even more of a worry for the 35,000 aircraft taking off and landing at Hong Kong International Airport every month.

“HKCAD is grossly undermanned with qualified inspectors,” agrees Chris Lee, a senior flight captain and a former department employee, who asks for his real name to be withheld. “They are very good at the bookwork and knowing the regulations, but don’t have that practical experience,” he says. “A lot of them have never held a command [made it to the rank of first officer]. It’s a horrible organisation to work for, with an old-fashioned Chinese bureaucratic mentality. They spend more time pushing paper than finding out what’s going on.”

An accredited air accident investigator, Newbery campaigns for incidents such as the Atlas Air near miss to be investigated by independent specialists rather than the CAD, but he takes a less alarmist line than Roberts and other senior pilots interviewed.

When asked to comment for this article, a CAD spokesperson says, “All accident investigators in CAD are properly trained, qualified and competent to perform their assigned duties,” adding,

“There is no ICAO nor statutory requirement that an accident investigator must be an experienced pilot.” Nevertheless, the spokesperson says all current investigators are experienced pilots.

When asked about the GFS’ failure to comply with MOR procedures and the current head of helicopter inspections, the spokesperson argues, “It is not appropriate for HKCAD to provide specific information about individuals. As far as aviation safety is concerned, HKCAD applies the same standards and requirements in regulating GFS as with other AOC [Aircraft Operating Certificate] holders.”

Adam Simpson, a Cathay Dragon (previously Dragonair) captain with 33 years’ experience who does not wish to have his real name published because of the effect that it could have on his career, would also like to see an independent body investigate serious Hong Kong incidents.

“Dragonair had a close encounter incident in 2011 in Hong Kong air space with a Cathay Pacific aircraft, but we are still waiting for the final investigation report,” he says. “There was a possibility that HKCAD might be implicated, so we have all had to wait. No one is regulating the regulator.”

Dragonair had a close encounter incident in 2011 in Hong Kong air space with a Cathay Pacific aircraft, but we are still waiting for the final investigation report

Newbery explains that, following recent changes to ICAO rules (known as Annex 13) and after some foot dragging, this air accident investigation body was officially proposed for Hong Kong by the government on June 7, and legislation is slowly progressing through the Legislative Council. If and when this legislation is passed, it should improve investigation of certain incidents, because independent experts will have no interest in leaving any aspects unexplored, but it will make little difference to the competence of the CAD and its day-to-day responsibility for aviation safety.

Another concern raised by Roberts and shared by others is that there is a predominance of ex-Cathay Pacific staff at the CAD.

“The ongoing joke in the industry is that CAD stands for ‘Cathay and Dragon’,” says Julian Crampton, an experienced Cathay Pacific pilot who also asks for his real name to be withheld. He says the general manager of operations at Cathay Pacific, Mark Hoey, has been granted authority by the CAD to interpret the airline’s Air Flight Time Limitation Scheme (AFTLS), which is crucial for determining the hours pilots fly and assessing their fatigue levels.

Cathay does not deny it is able to set its own limits but insists it “develops AFTLS based on the CAD 371 (2nd Edition) mandated by the HKCAD”, and says the same rules apply to other operators in Hong Kong.

Beebe also points out that the CAD does not sit on Cathay Pacific’s Fatigue Risk Management System (FRMS) committee. That may sound like a minor administrative detail but such committees are an important means by which to monitor and manage pilot fatigue, which is regarded as a major contributory factor to accidents. They should involve the service provider, pilots and the regulator.

“I cannot think of a logical reason why HKCAD would not sit on this key safety committee related to pilot fatigue,” says Beebe, and Newbery goes further.

“As the recent decision to utilise two second officers on long-haul flights demonstrates, Cathay is quite capable of bypassing the whole [FRMS] in the interests of short-term financial savings,” Newbery says, referring to the airline’s controversial plans to dispense with a more experienced first officer on some routes. “This plan [...] had fatigue and safety implications and so should have undergone an assessment by the FRMS, which is set up to do exactly this kind of work. However, the FRMS was bypassed and the decision was made by senior managers without any kind of transparent risk assessment.”

The operation at Atlas is falling apart because of chronic mismanagement, a shortage of pilots and a lack of other key operational personnel

Safety, insists a Cathay Pacific spokesperson, is always our top priority, adding, “Any operational changes have to go through a thorough and vigorous review to ensure that safety is never compromised, which remains the case in this new arrangement.”

The CAD spokesperson says, “In terms of regulating Air Operator’s Certificate holders in Hong Kong, HKCAD has established a rigorous mechanism for the issue of AOC and surveillance of AOC holders and their operation.”

The Atlas Air aircraft involved in the Lantau incident had been “wet leased” to Cathay Pacific and Atlas, like all airlines operating locally, had been issued its AOC by the CAD.However, Atlas Air is mired in controversy and involved in a bitter industrial and legal dispute with its own pilots over issues related to fatigue, reported illness levels and manning. “The operation at Atlas is falling apart because of chronic mismanagement, a shortage of pilots and a lack of other key operational personnel,” Captain Robert Kirchner, a long-time Atlas pilot, told United States media on October 7.

With an unproven air traffic control system, an airport at near full capacity, rapidly expanding mainland carriers, an international pilot shortage and widespread cost-cutting exercises all potentially affecting passenger safety, the need for a robust and proactive regulatory body in Hong Kong is more acute than ever.

Instead, Roberts claims, there are serious flaws at the heart of aviation safety that urgently need addressing before a catastrophe occurs.

“The trouble is,” he says. “when the safety alarm bells go off, no one at HKCAD seems to hear them.”