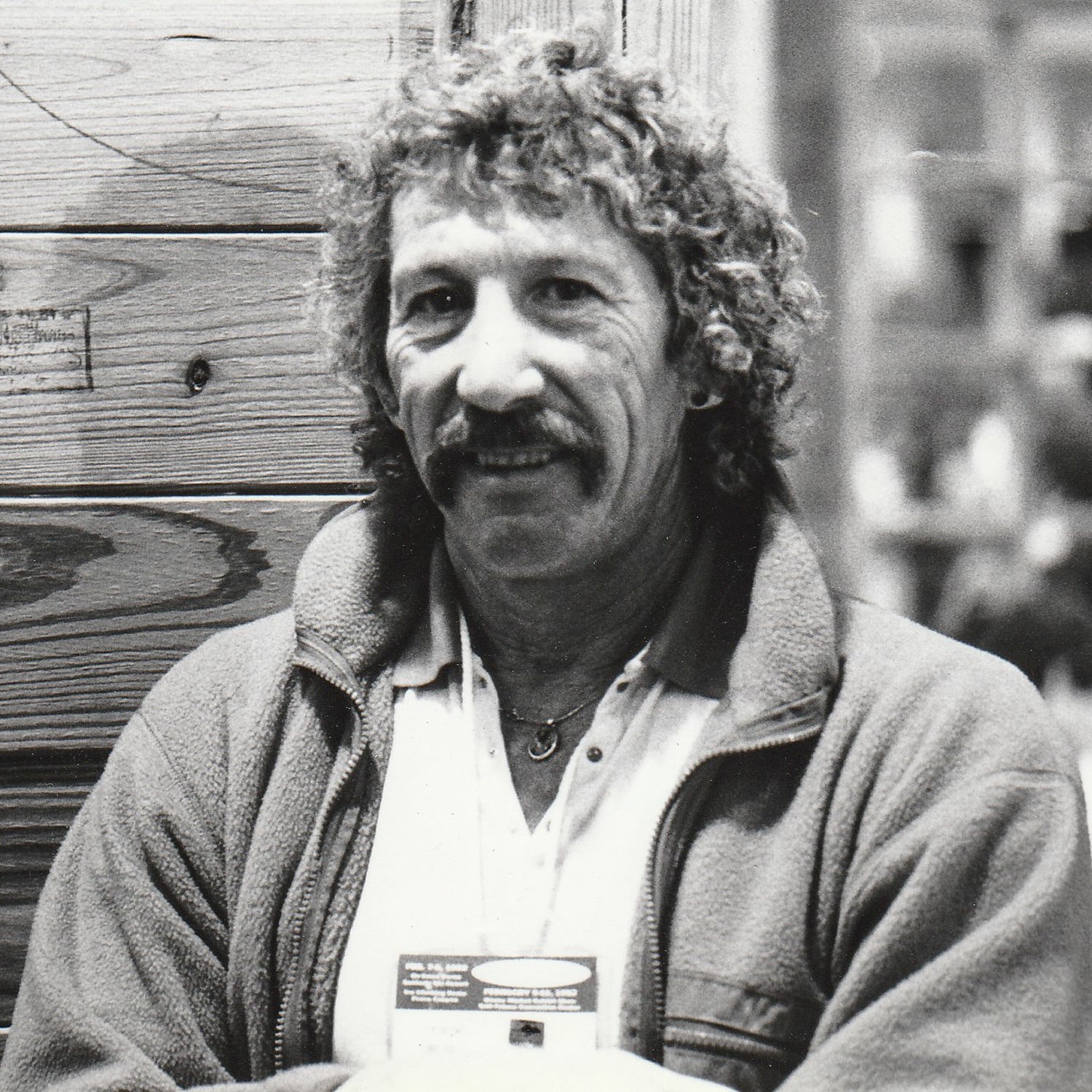

In the 60-year history of modern Yosemite rock climbing, the sport’s all-time greatest cultural hero was Jim Bridwell, who died of complications from hepatitis C on February 16 at age 73.

The Valley has had other heroes, to be sure. Clean-cut Royal Robbins, who died late last year, created the enduring image of the climber as earnest moral seeker. The powerfully athletic Lynn Hill, who became the first person to free-climb El Capitan in 1993—meaning she used ropes only for safety, and made all upward progress with hands and feet on rock—filled the climbing world with pride that great female climbers could be every bit as good and sometimes better than the best men. But in the same way that Jimi Hendrix remains the model for every rock-n-roll guitarist, Jim Bridwell, with his excellent mustache and deep presence, towers above all the others as the ultimate embodiment of climber cool.

Bridwell was born in 1944 in San Antonio, Texas. His father was a pilot in World War II and later flew for commercial airlines, while his mother was a sometimes artist. Bridwell first climbed in Yosemite in 1965, when the sport’s culture was gelling around the campground known as Camp 4, and when titans of the sport like Robbins, Yvon Chouinard, and Warren Harding were making first ascents of the Valley’s most prominent walls. By the early 1970s, Bridwell had become the undisputed leader of the next generation.

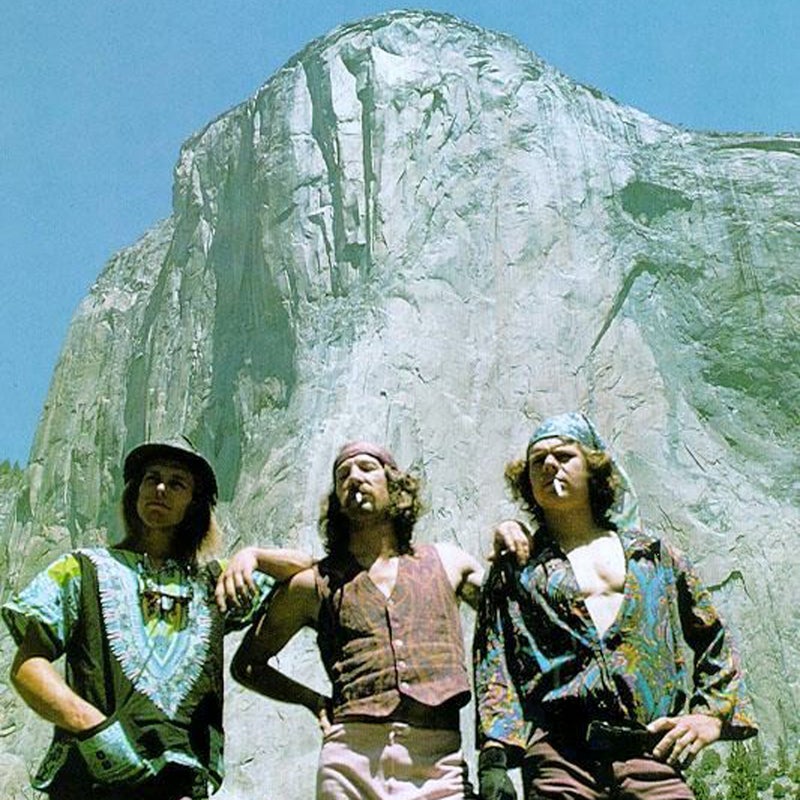

In 1975, with John Long and Billy Westbay, Bridwell made the first one-day ascent of El Capitan, via the Nose route, which still takes most climbers three or four days. Their achievement still echoes through the international obsession with speed records on big climbs all over the world—the current record on the Nose has been whittled down to a blazing 2:19. Bridwell also ushered in a new era in aid climbing, in which upward progress is made by fixing gear into the rock, attaching stirrups to that gear, and then standing in those stirrups to place the next piece of gear.

Peter Mayfield, director of the Gateway Mountain Center near Lake Tahoe, and a longtime climbing partner of Bridwell’s, points out that the generation before Bridwell did first ascents on the great cliffs by tackling “big features, lines of least resistance” where prominent cracks allowed climbers to hammer in pitons secure enough to hold falls. When climbers of that earlier generation reached long sections too smooth for secure piton placements, they often drilled holes to place permanent safety bolts. Bridwell, in order to break new ground for his own first ascents, found new ways up vast smooth sections where stable piton placements were scarce or non-existent, and mostly without drilling the safety bolts that eliminate danger and adventure.

“He really pioneered the climbing of the smaller not-even-features, little ripples and incipient seams,” says Mayfield.

Bridwell became the first great master of extreme aid-climbing tools like copperheads, little lumps of soft copper swaged onto wire loops. Bridwell and his partners became adept at placing those lumps of copper against faint indentations in the rock and then striking them with a hammer to mash that soft metal against the cliff. The climber would then clip stirrups to the wire loop hanging off that mashed metal, stand in those stirrups—very gingerly, so as not to rip the copperhead off the wall—and then bash another, and another, sometimes for a hundred feet or more without placing a single piece of gear that could hold even a short fall.

Bridwell’s greatest first ascents, including the routes Zenyatta Mondatta and Sea of Dreams, both on El Capitan, included such long stretches of extreme aid climbing that even a small mistake, like a brief loss of balance that caused a jerk on the rope, could tear out whatever copperhead he was hanging from and send him on a 200-foot fall ripping out every copperhead along the way. In some cases, those falls had the potential for grievous impact with rock features below.

Bridwell made important first ascents elsewhere, too, like on Cerro Torre in Patagonia and the east face of the Moose’s Tooth, in Alaska, but his enduring role as cultural hero derived as much from Bridwell’s personal style and the sheer force of his personality. The single most iconic photograph in Yosemite climbing history captures Bridwell and his younger partners, John Long and Billy Westbay, after that first one-day ascent of El Capitan’s Nose Route in 1975, and it resonates as much for the climbing accomplishment as for attitude. Wearing wild paisley shirts and bell-bottomed pants, smoking cigarettes and posing with rebellious insouciance, Bridwell and his partners created an utterly new image of the rock climber as biker-hippy-hardass, letting their freak flags fly while doing stuff harder and more terrifying than anything done before. Rumors of LSD trips during rest days in the middle of big first ascents added a very 1970s sense of extreme seeking, as did Bridwell’s route names: Sea of Dreams, of course, but also Aquarian Wall, Dark Star, and the Dance of the Woo-Li Masters, named for the 1979 bestselling book about quantum physics, The Dancing Wu Li Masters.

Bridwell never managed to convert his accomplishments or his image into lucrative sponsorships or business opportunities as many of his contemporaries did, and this was a well-known source of frustration in his life. But he always remained a natural leader and great mentor, deeply admired by the many younger climbers he encouraged. Mayfield, who was 18 when he joined Bridwell on Zenyatta Mondatta, recalls taking a 40-foot fall on that route only to have Bridwell say, “You know, I see you up there pussyfooting around trying to be delicate, and that’s not the way to climb this stuff. You got to take that hammer and bash the shit out of that diorite until the loose outer rock comes down and you get to the solid stuff underneath.”

“I said, ‘Okay, let me at it,” Mayfield recalls. “I went right back up there and swung my hammer hard and he was right.”

Despite Bridwell’s hard-and-wild appearance, Mayfield insists that he was a flawlessly safe climber, and that his temperament was mostly “sweet and soulful.”

In the late 1980s, European-style sport climbing first came into vogue. It emphasized minimizing danger in order to maximize the potential for extreme gymnastic difficulty on tiny handholds and footholds. As part of this new wave, climbers putting up new routes often hung from ropes to pre-drill protection bolts before attempting their ascents. This was a grave violation of traditional Yosemite climbing ethics, which dictated placing protection gear only from the ground up. According to Mayfield, when two Bridwell protégés came to blows over the issue, Bridwell told them, “On your dying day you are not going to give a shit about how hard you climbed. You’re only going to care about who you connected with and how many people you helped along the way.”

In his own final hours, surrounded by family, Bridwell surely remembered that he’d connected with and helped far more than most.