Ed Harris: ‘His plays allow you to pour it out’

Sam had just won the Pulitzer prize for Buried Child and was already a bit of an icon when we first met. I did Cowboy Mouth, which he wrote with Patti Smith, in a little theatre in LA in 1979 and he came around to rehearsals. Then I was in his play True West, and we went for a few beers, played some pool.

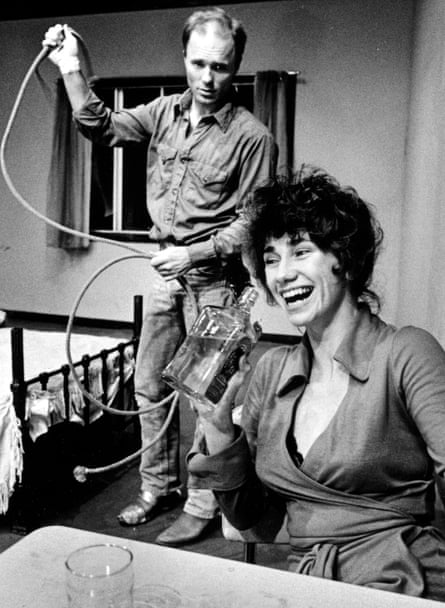

Fool for Love, which Kathy Baker and I did in 1983, was a really fun time. That play allows you to just go out there and pour it out. I was a pretty young guy and we were kicking ass every night. For a young actor, the part of Eddie is a joy. He’s a rodeo cowboy, in trouble with the woman he loves and trying to win her back. You learn how to use a rope, put your spurs on, and go out there and wail on it. There’s a lot going on inside that guy. Most of Sam’s plays are pretty autobiographical in terms of dealing with his own internal maelstrom. His last book, The One Inside, is a collection of episodic little stories tied together. It’s the most intimate thing he wrote. Read that and it’s like you’re holding the essence of Sam in your hands.

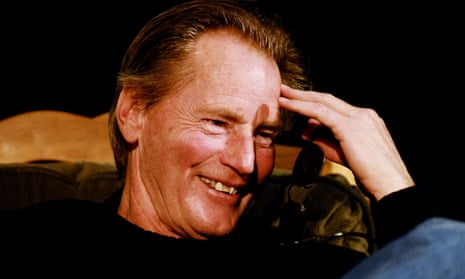

Sam was a man who did not relinquish power, but in his work he allowed himself to be vulnerable and uncertain. He looked at life knowing it’s transitory and full of surprises, and he understood what a labyrinth the human psyche is. It was a joy to work on his plays because of the poetry and rhythm of the dialogue. Exploring his characters is like a bottomless pit. We just did 125 performances of Buried Child in London and were still discovering things about these people at the end of the run.

I think he trusted me. Sam really liked actors. He’d cast people he knew could inhabit these characters and he’d say what was necessary to guide you to find the truth. I only saw him on stage once, in Caryl Churchill’s A Number in 2004. I always felt he believed in simplicity and stillness and just let the language work for him. He had a great presence. In his later years he started to play some great character roles, like in Mud (2013). He knew he was getting older and didn’t have those matinee idol looks any more, and played these characters that were kind of quirky and strange. It was fun to see him inhabit them.

As a really private guy, Sam didn’t talk a lot about his feelings. I’m glad I was able to spend some time with him when we were rehearsing Buried Child. He’d been diagnosed with ALS [Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis]. When he found out he was seriously ill, he became more open and accessible. A kindness crept into him. It allowed me to feel the nature of our friendship, and I’d like to think it was the same for him. He was a huge influence in my life. I loved the guy and I’ll miss him big time.

Kathy Burke: ‘It was beautiful of him to reassure me’

I got to speak with Sam on the phone a few times when I directed The God of Hell in London (famously he didn’t fly or have the internet). A couple of calls stand out in my mind – firstly, my ringing him to apologise for the bad reviews the play had received.

ME: I’m so sorry I’ve let you down. They hate what I’ve done with it here.

SAM: Please don’t apologise, Kathy, they hated it over here too!

The following week, he called me:

SAM: I wanted you to know I’ve just had a call from a friend who saw the show last night. He thought you did a terrific job. He said it was like you KNOW me, so thank you, Kathy, I appreciate your hard work.

He didn’t have to do that. It was charming and beautiful of him to reassure me.

Lynn Nottage: ‘He told me to own all of my words’

At a time when people were writing plays set in living rooms and gardens, Sam Shepard’s were set in backyards and motels. He took us to a different kind of landscape that hadn’t been explored on the American stage. More than most, he figured out a way to speak to the restlessness of a generation in the 70s and 80s.

I had a one-off encounter with him in Utah. I’m a playwright, not much of a performer, and I had decided to perform some of my own writing. I picked a very remote setting where I figured no one would know me. It was at a bar at about 10pm. When I got there, I was the only person of colour. My piece was about all the times in my life that I’ve been called the N-word. People were pretty drunk. It was almost like doing a comedy night. I was extremely nervous but I muscled through. When I was done, I was sweating profusely. I went immediately to the bar and ordered a drink and someone said: “Can I give you a piece of advice?” I looked up and it was Sam Shepard and I was like, Oh shit! It’s Sam Shepard – of course you can give me a piece of advice!

I guess he was there because he was making a movie. He bought me a drink and we ended up hanging out until 3am. He said he could tell I was really nervous and he was like: “Fuck these people. This is your writing. Next time you do it, you have to live every single moment and own all of your words. And not be intimidated, not be scared.” I’ve always clung to that advice.

Matthew Warchus: ‘He found extremity and folly funny’

When I directed True West in 1994 at West Yorkshire Playhouse, I alternated the roles of the two brothers. Sam heard about it and sent a message to me enthusing about the idea. Then, when I was preparing to direct the film adaptation of Simpatico, I met him for the first time in a restaurant in New York. He was sitting there – leather jacket, windswept hair, rugged looks – and it was like meeting a cowboy.

When I was a teenager I had watched True West on TV, sitting on the sofa at home in a village in the middle of nowhere in North Yorkshire. I don’t think I spoke for about 48 hours after seeing it. On one level, that world of the American west was a long way from my own bleak, arable landscape. But I felt this weird, strong connection to it. And Sam was fascinated with England and with Europe. So we were extraordinarily different to each other but had much in common. Like me, he loved Yasmina Reza’s plays. There is a lot of wildness in her writing, which looks at the catastrophic breakdown of civilised behaviour. He found extremity and folly to be funny in the same way that she does. He was always chortling – he had a great sense of humour.

Sam spoke with a drawl. Talking to him, it was as if you were out camping somewhere together, sitting by the fire. He once sent me a note saying maybe we could meet up and “break some bread” – I’ve never heard anyone else use that expression. When he read from his own work, there’d be an incredibly precise, articulated voice mixed in with that drawl and he’d use that when he was reading women. His voice could be surprisingly high-pitched. He read women really beautifully, which I always found strange for someone as snaggle-toothed as he was.

I once visited him at his home in Minnesota. It was on 9/11. My then girlfriend (now wife) and I were travelling to Bismarck, North Dakota, but were stranded at Chicago airport. We got the last rental car and started driving. Twelve hours or so into it, I thought, this is a very Sam Shepard thing to be doing on such an extraordinary day in American history. And I realised we weren’t far from where he lived. I called him and said I thought we were close to his home. He gave me directions and we pulled up at his suburban house. We went up the garden path, met him and Jessica [Lange, his partner] and the TV was on showing the twin towers. We sat there watching it and drinking English tea.

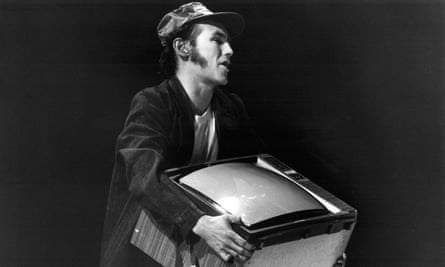

Unlike some writers who balance theatre and film careers, his formative experience with the theatre was off-off-off-Broadway. He was really a part of the underground and alternative movement. Almost all of his theatre-making was like that. That’s a total difference to the world of Hollywood.

When I was preparing Simpatico, we talked a lot about horses. That was one of his great loves – along with driving long distances. He’d really light up on those subjects. Sam was a drifter: he’d appear for a few days in New York, hover at the back of a performance, laugh and drink and move on.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion