'Secrets' over Patrick 'Guiseppe' Conlon's pub bomb prison death

- Published

The government drew up a secret plan to release a man wrongly convicted over IRA bombs in Guildford, papers seen by the BBC reveal.

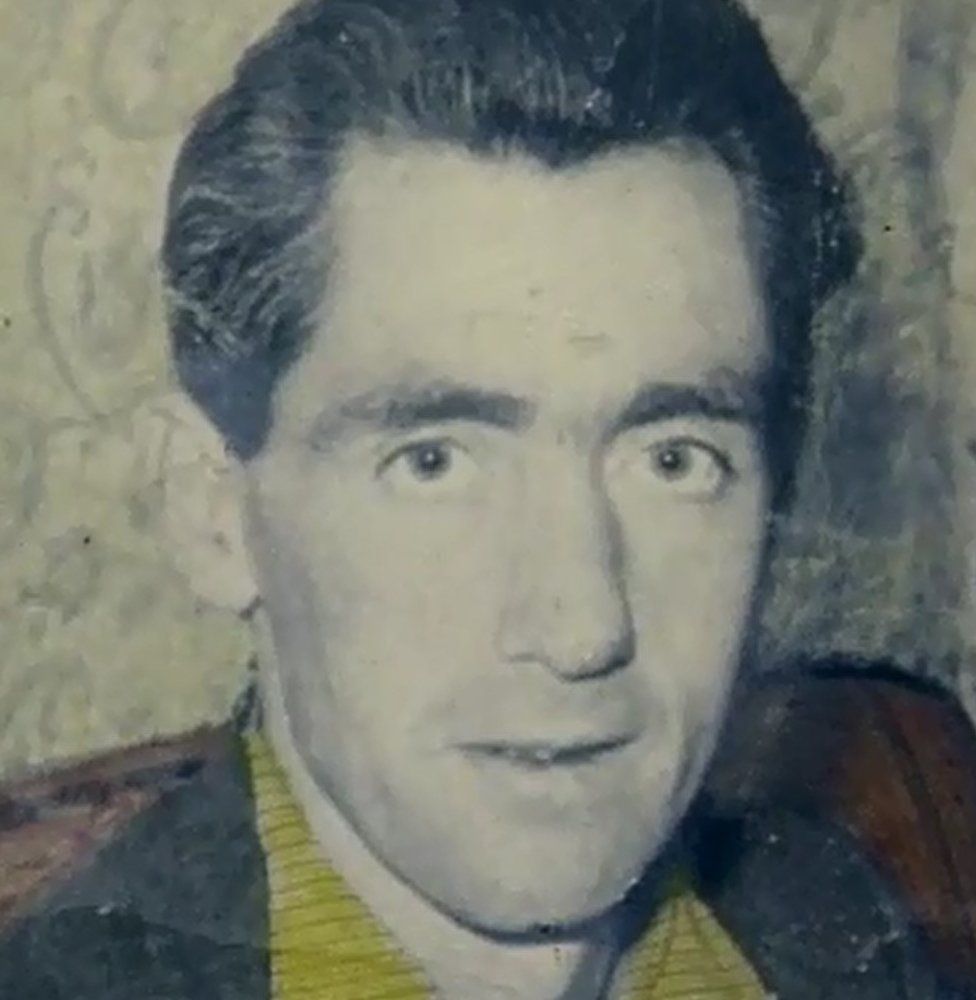

Belfast man Patrick "Guiseppe" Conlon was jailed with his son and nine others after two explosions in Guildford in 1974, and died of tuberculosis in 1980.

But had he recovered, he would have been released from jail, papers show.

His family said the attempt to hide the details was "horrific". The government declined to comment to the BBC.

Mr Conlon was one of the Maguire Seven, convicted on explosives charges, and his son Gerry was one of the Guildford Four, jailed for murder after the pub bombings killed five and injured 65.

All eventually had their convictions quashed after what became known as one of Britain's biggest miscarriages of justice, and the story told in the film In The Name of the Father, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Pete Postlethwaite.

It was reported by the BBC Mr Conlon's health became so poor in December 1979 he was taken to hospital, but just over a week later was returned to jail.

He was again moved from prison to hospital as his health worsened and died on 23 January 1980, the same day Home Secretary William Whitelaw - later Lord Whitelaw - decided to grant him parole.

The BBC has seen the private papers of his predecessor Merlyn Rees - later Lord Rees - including some files that remain closed to the general public.

One file contained a letter from Lord Whitelaw to Cardinal Basil Hume, who had campaigned on behalf of the 11.

Writing the day after Mr Conlon died aged 56, four years into his 12-year prison term, he said: "Although it will be of no comfort to his family I thought you should know in confidence that I had in fact already come to the conclusion that should Mr Conlon recover sufficiently to be discharged from hospital, it would not be right to return him to prison."

Further letters revealed how the decision was leaked to the press after the government tried to keep it private.

Mr Conlon's granddaughter Sarah McIlhone said her mother, Ann McKernan, was too ill to comment, but would demand the truth needed to be told.

"This is horrific. My granddad and my uncle Gerry were innocent men," Ms McIlhone said.

"The whole family suffered awful pain and heartache because of what the British government have done. We don't know what to say."

'Lasting heartache'

Patrick Conlon was arrested after his son Gerry's false confessions, which he alleged were made as a result of police brutality.

In 2016, after the BBC accessed files on the case, Ann McKernan described how her brother was left feeling lasting guilt over what had happened to their father.

"Nobody's seen his tears, but I've seen his tears," she said.

"He blamed himself for my father's death, and he cried to me, and I couldn't take that heartache away."

Christopher Stanley, from KRW Law which represents the Conlon family, said: "This sad revelation confirms again the demand for truth and justice regarding both the Guildford pub bombings and the wrongful conviction of the Guildford Four."

He has successfully applied to the Surrey Coroner for a fresh hearing - a pre-inquest review - into the bombings.

Richard O'Rawe, a former Irish republican prisoner who grew up with Gerry Conlon in Belfast, said: "We thought we were beyond shock, we are not.

"The British government should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves in the way they have treated the Conlon family."

Human rights lawyer Alastair Logan, who previously represented the Conlons, believes the secrecy suggests the government was "covering themselves", and said the important matter was what it knew about Mr Conlon's condition.

"Their decision to retain him in prison must have been made with the knowledge that it was highly likely he would die in prison - and he did," he said.

Mr Logan said when Mr Conlon was in Wakefield Prison, he believed his condition was chronic and would inevitably lead to his death, and by the time he reached Wormwood Scrubs it was much worse.

He said arrangements were not even made to give Mr Conlon meals when he could not make it down the stairs from the third floor of Wakefield Prison to the ground floor to eat.

Fellow prisoners saved up their meagre wages to buy him the food supplement Complan, he added.

The government had said in 1976 that Mr Conlon's health was "satisfactory" and in April 1979 said medical reports deemed him fit to remain in jail.

Inquest reports in 1980 said the Prison Service tried to treat Mr Conlon several times for a chest illness, but he died of natural causes from heart failure caused by his condition.

The family always claimed Mr Conlon was only given non-prescription cough medicine.

Descriptions over Mr Conlon's condition have varied over the years to include TB, lung cancer and emphysema. Documents in the files attributed his death to TB.

Treatment given now for TB involves taking antibiotics for several months.

The NHS website states: "With treatment, TB can almost always be cured."

The BBC has asked to see any of Mr Conlon's medical reports from 1979 that may still exist.

Related Topics

- Published8 November 2017

- Published23 January 2018

- Published27 October 2016