You wait years for a historical theory to be debunked and then three come around at once. So far this week, we have been told that the mysterious pestilence that wiped out 15 million Aztecs between 1545 and 1550 was not smallpox or measles, but enteric fever, that the Black Death was spread by fleas and lice from humans as well as rat fleas (a theory that, in truth, has been around for a while), and that the supposed origins of the phrase “whipping boy” (where surrogates were punished in place of young royals) seem to be false. In the spirit of debunking myths, here is my (in no way exhaustive) list of 10 historical “mythconceptions”.

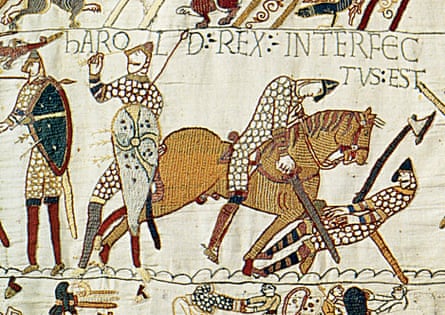

Mythconception #1: Harold took one in the eye at Hastings

It seems like one of the most certain facts in English history, but accounts relating to Harold Godwinson’s death vary considerably. Some sources simply state that he was killed in battle. The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, written shortly after the battle, goes a little further and details how he was lanced in the chest, beheaded and had his entrails “liquefied” with a spear. It was not until the 12th century that chroniclers started to claim that he was killed by an arrow through the eye. Scholars believe this is in part due to reports about the sophisticated archers present at the battle, but also because of the image believed to be Harold Godwinson on the Bayeux tapestry (which you will soon be able to see in the UK). Created shortly after the battle, the tapestry shows two figures under the inscription: “Harold the King is killed.” The first figure has an arrow in his head, the second is being trampled by a horse. Is the first man Harold? Is the second? Could the figures show Harold’s death in sequence? There is no consensus.

Mythconception #2: We think we know the Queen of Sheba

The Queen of Sheba is perhaps second only to Cleopatra when it comes to historical female notoriety. Yet, despite the power of her legend and the fact that she appears in Christian, Islamic and Jewish texts, little is known about the real figure behind the tale. In the biblical story, she is presented as an independent sovereign who visits King Solomon and brings with her gifts of gold, precious stones and spices. Some scholars believe she may have been the ruler of a kingdom called Saba, in what is now modern-day Yemen. Another theory anchors the Queen of Sheba to Ethiopia. According to the Ethiopian national epic Kebra Nagast, she was Queen Makeda who bore King Solomon a son, Emperor Menelik I, the founder of the Solomonic dynasty.

Mythconception #3: Columbus ‘discovered’ America

In popular imagination, the first European to “discover” America was Christopher Columbus in 1492. Yet there is evidence of a European presence in the Americas that precedes Columbus by several centuries. It is thought that the first European to discover America was a Norse explorer named Leif Erikson who voyaged from Greenland to what is now Canada in about AD1000. The theory is supported by carbon-dated archaeological discoveries at the site of L’Anse aux Meadows in Canada.

Mythconception #4: Genghis Khan was an unsophisticated warlord

In popular culture, Genghis Khan is remembered as a barbaric caricature of a brutal and hot-headed warlord. While it is certainly true that a mixture of conquest and bloodshed (some estimate he was responsible for up to 40m deaths) saw him preside over the largest land empire the world has ever known, the caricature suggests a lack of sophistication and forward planning which is at odds with reality. Genghis Khan used a combination of military might, ruthlessness, psychological warfare and terror to dominate his enemies – from lighting extra fires to give the impression of a larger army to promoting soldiers on merit rather than social standing. All of this was bound together by a sophisticated postal system that enabled him to gather and send information in record time.

Mythconception #5: The Glorious Revolution wasn’t as glorious as advertised

In 1688, William of Orange invaded Britain, overthrew his father-in-law, James II of England, and (in 1689) became joint sovereign of England, Scotland and Ireland. According to the 19th-century historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was “bloodless, consensual, aristocratic and, above all, sensible”. Yet the truth of the revolution is far from bloodless. In Reading, 50 men were killed during an uprising. In Scotland, it exacerbated tensions between Lowlanders and the Highlanders, resulting in a number of rebellions and plots, and was linked to the Glencoe massacre. In Ireland, it provoked a land war – with William and James leading opposing sides at the Battle of the Boyne – which cost many people their lives. William’s ultimate victory entrenched centuries of religious division.

Mythconception #6: The free press was a man’s game

This is not so much a myth as a surprisingly unknown fact. For those interested in the history of journalism and printed news, a few names stand out. There is Johannes Gutenberg, the man who kickstarted the print revolution in Europe; there are Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift, the early innovators of professional journalism in Great Britain; and there are pioneers of investigative journalism, such as WT Stead. Ask who created the first daily newspaper, however, and you are likely to draw a blank. It was, in fact, established in 1702 by a woman named Elizabeth Mallet, who assembled and published it at her printing house on Black Horse Alley, near Fleet Bridge in London. In the first edition of what was known as the Daily Courant, Mallet wisely asserted that she would: “Relate only matter of fact; supposing other people to have sense enough to make reflections for themselves.”

Mythconception #7: Women in medicine started with the Lady with the Lamp

For many, the story of women and medical care begins with Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale, who are rightly remembered for their pioneering work in reforming 19th-century nursing. But, as medical practitioners, women have a rich and varied history that stretches much further back than the 1800s – from the groundbreaking medical writings and practices of the 12th-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen and the astonishing career of Dr Laura Bassi, who held the position of professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna in 1732, to the hundreds of everyday medical practitioners conducting blood-letting, prescribing treatments, examining urine and conducting abortions and surgery during the early modern period.

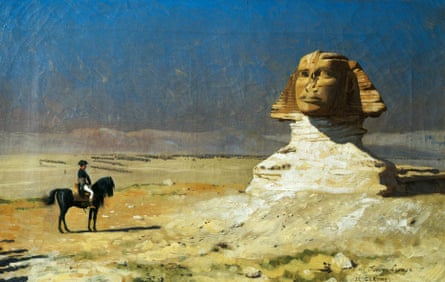

Mythconception #8: Napoleon knocked off the Sphinx’s nose

Legend has it that when Napoleon’s expedition reached Egypt in 1798, some of his soldiers knocked off the Sphinx’s nose during a spot of target practice. It is a fun story, but untrue. Drawings of the Sphinx by a Danish naval captain named Frederic Louis Norden, created decades before Napoleon was even born, clearly show the Sphinx without a nose. Going further back, Egyptian historian Al-Maqrizi commented on the missing nose in the 15th century. How the nose came to be destroyed is still debated, with theories ranging from weather erosion to iconoclasm.

Mythconception #9: The Wright brothers were first to take to the skies

The Wright brothers may lay claim to making the first controlled, heavier than air, manned flight in 1903, but they were by no means the first humans to take to the skies. Perhaps the most significant aviation breakthrough occurred in 1783 when the Montgolfier brothers successfully orchestrated the manned flight of a hot-air balloon in France. In a short space of time, manned hot air balloons became so ubiquitous that they were used for observational military purposes during the French Revolutionary wars. The first recorded use in this way occurred during the Battle of Fleurus in 1794 and “observational balloons” continued to be used during the American civil war and the first world war.

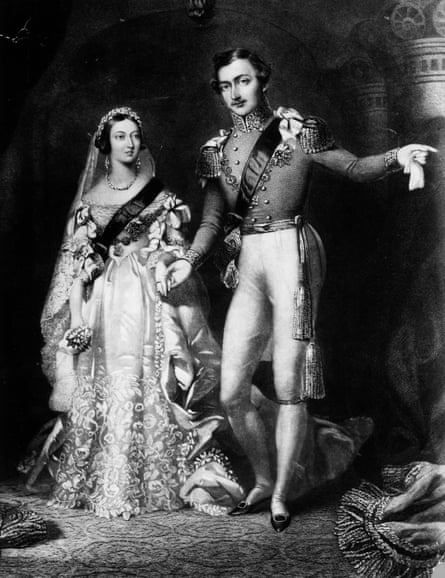

Mythconception #10: The Victorians were prudes

One of the most stubborn myths about the Victorians is that they were sexual prudes. This is, in part, thanks to contemporaneous ideas such as The Angel in the House and the very real legal inequality between men and women. However, Victorians were quite direct in affairs of the flesh. Queen Victoria wrote in her diary, for example, how Prince Albert had “clasped me in his arms and we kissed each other again and again”. As the historian Fern Riddell notes: “The Victorians were the opposite of prudes, this is the era of women publishing guides to contraception, and a belief that female sexual pleasure was paramount to a healthy and happy relationship. Too often we have only looked at the Victorians through legal, medicinal or scientific attitudes to sex, but every day sexual culture was vastly different.”

Rebecca Rideal is a writer, freelance television producer and historian. Her book, 1666: Plague, War and Hellfire, is published by John Murray (UK) and St Martin Press (US).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion