What you need to know

Democratic societies like Taiwan can still fall victim to an authoritarian corporate environment.

This is the third in a 5 part series. You can read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Authoritarianism, tax and profit

The absence of external checks on government described in part 2 inspires little faith given that the government has such high control of the largest companies in Singapore. Can companies be expected to act for the benefit of their workers without public scrutiny or government guidance? Evidently not, given the low (de facto) minimum wages in Singapore, and as we will soon see, the miserable social protection offered to Singaporeans.

Whereas the mistake the international community makes is misunderstanding how Singapore is run, the mistake with regards Taiwan stems from not understanding that despite being politically democratic, Taiwan is corporately and, to some extent, socially authoritarian.

Such a view explains the wage-welfare dynamics in the country. In Taiwan, there remains hope that its democratic system can help dispel these last vestiges of authoritarianism following the lifting of martial law in 1987, though this is hindered in both the boardroom and society by a Confucian culture and rigid adherence to hierarchy.

On the other hand, Singapore’s authoritarianism is intertwined in its political, corporate and economic infrastructure, which serves only to further entrench it. In Hong Kong, it seems that corporate authoritarianism has overpowered politics. Whereas previously the corporate sector had been willing to tolerate supporting social welfare at the behest of political leaders, a new reality is now in play given the increasing influence of China, which functions in much the same way as Singapore.

In fact, Hofstede's 6-D model of national culture, which looks at the way societies are structured along six dimensions of culture, shows the correlation between higher Power Distance in a society – and thus greater hierarchy and authoritarianism – and inequality. Hofstede defines Power Distance as “the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.”

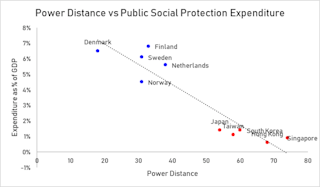

Indeed, in countries where Power Distance is higher, their governments’ commitment to reducing inequality is lower, according to Oxfam International’s “Commitment to Reducing Inequality” report. Not only that, an ILO study shows their governments tend to spend less on social protections and tolerate greater cronyism in society. Purchasing power and social mobility are also lower. The chart below provides a snapshot of the correlations.

Source: Geert Hofstede, ILO.

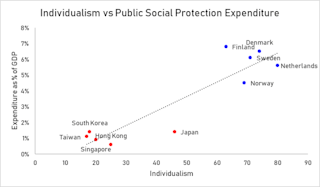

Hofstede also found that when individualism is low, governments spend less on social protection and are less committed to reducing income inequality, while purchasing power and social mobility are again depressed.

Source: Geert Hofstede, ILO.

Individualism is defined by Hofstede as, “the extent to which people feel independent, as opposed to being interdependent as members of larger wholes.” Interestingly, East Asian societies have a knack of promoting “Asian values” with an eye to suppressing individualism while claiming that their collectivist cultures entail a willingness to comply to top-down hierarchy and obedience to elders.

But this individualism-collectivism dichotomy might be a mirage indoctrinated into the citizens of the East Asian countries. The Nordics are said to be individualistic and their scores on Hofstede’s scale confirm this notion, but they are at the same time collectivist.

Collective bargaining has ensured higher wages in the Nordics. Are the East Asian governments therefore using collectivism as justification to disregard their citizens’ rights for better social protections?

The culture of calling one another “senior (學長)” and “junior (學弟)” in Taiwan’s society could therefore be toxic in the long term as it serves to further entrench the mindset of hierarchy – and Power Distance – and an enforced collectivism (while diminishing the awareness of citizens of their individualism). This keeps citizens in their places and erodes their ability to fight for their rights – and hence higher wages and better social protections. For the Asian Tigers to move towards the equality that the Nordics have been able to achieve would require their citizens to look at one another as equals, and not in terms of who is superior to who.

Last year, a paper published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that, “tax cuts for higher income groups […] exacerbate income polarization and inequality, both already at historical highs,” and that, “lowering personal income tax rates [for the higher income groups] does not raise growth enough to offset the revenue loss that is caused by the tax cut itself.” In fact, the IMF found that, “higher income tax rates for the rich would help reduce inequality without having an adverse impact on growth.”

On the other hand, the IMF found that tax cuts for the lower and middle income groups would help to stimulate economic growth and reduce income inequality. The IMF therefore advocated for “progressive taxation and transfers [as] key components of efficient fiscal redistribution.”

This is why the amendments to Taiwan’s Income Tax Act earlier this year, which cut the highest income tax rate to 40 percent from 45 percent (having only increased it three years ago), are problematic. One has to wonder what the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is trying to do – shouldn’t it be on the workers’ side?

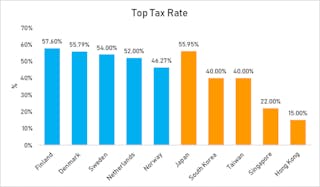

As it stands, the top tax rate in Taiwan is already lower than in the Nordics, the Netherlands and Japan. (Taiwan might have a similar top tax rate with South Korea but South Korea’s wage gap is lower than Taiwan’s and the top families' control over the economy is lower, which reduces the negative side effects.)

Source (data from latest year): KPMG.

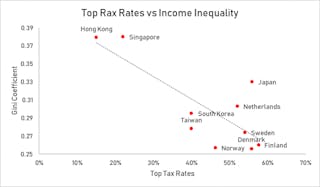

Moreover, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research has found that in countries with lower top tax rates, income inequality is also higher, which we similarly confirmed. This is a situation that Taiwan’s latest tax amendment will undoubtedly worsen.

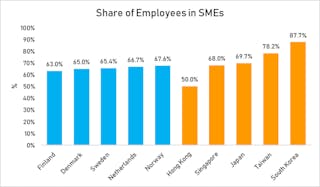

Other than a problematic high concentration of family control in big businesses, there is another indicator that deserves closer attention – the share of employees in the country employed by SMEs.

In the Nordics and the Netherlands as well as Japan and Singapore, the share of SME employees is about 60 percent. In Hong Kong, it is about 50 percent, though this does not include the civil service. But in South Korea, the share is 87.7 percent and in Taiwan, it is also high – 78.19 percent.

Source (data from latest year): Eurostat, Japan, South Korea and Singapore: Asian Development Bank, Taiwan: Small and Medium Enterprise Administration Ministry of Economic Affairs Taiwan, Hong Kong: Support and Consultation Centre for Small and Medium Enterprises Trade and Industry Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

A common refrain of the Taiwanese government is that minimum wages cannot be spiked up because “extreme minimum wage hikes can result in shutdowns of small and medium-sized businesses and layoffs at large companies,” Vice Premier Shih Jun-ji (施俊吉) was recently reported as saying. He pointed to the example of South Korea, which increased its minimum wage by 16 percent last year.

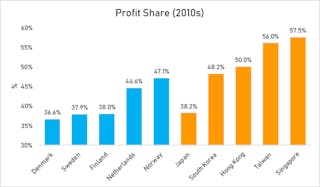

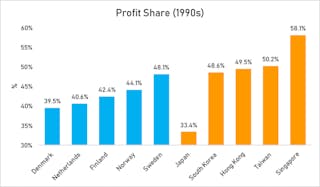

With a similarly high share of employees in SMEs in Taiwan, this might be a cause for concern. But the fact is that there is one main structural difference between Taiwan and South Korea – Taiwan’s profit share is high. From 1990 to 2016, while Taiwan’s wage share has declined, its profit share (the share of GDP that does not go to wages) has increased from 48.96 percent in 1992 to 56.19 percent in 2016. Wages are not being returned to the workers, and the government’s complacency in not protecting workers’ right to enjoy the benefits of their toil is in part to blame.

As compared with the Nordics, Japan and South Korea, and even Hong Kong, where profit share is less than 50 percent, Taiwan’s companies look to be earning even higher profits. To take an example, Taiwan's Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) was last year ranked as having the ninth highest profit per employee in the world.

Source: OECD Statistics Working Papers, Taiwan: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), Executive Yuan, (R.O.C. Taiwan), Hong Kong: Hong Kong Economy The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore.

Moreover, even in the 1990s when Taiwan’s profit share started to edge up, Taiwan’s businesses were already earning higher profits than the Nordics, Japan and South Korea, and even Hong Kong, though not as much as Singapore.

Taiwan’s profit share of 50.2 percent in the 1990s was higher than the other countries (except Singapore), which had shares of less than 50 percent.

In short, workers in Taiwan are being hoodwinked of their wages. Needless to say, Singaporean workers have it worse off.

As pointed out in another report by the ILO, “higher profit shares (lower wage shares) did not yield significant gains in investment. In fact, the main lesson from the literature is that the majority of countries are wage-led, including economic zones such as the euro area.

“In other words, wage restraint does not lead to higher economic growth. Importantly, wages constitute the main source of income underpinning private consumption and therefore the possibility for firms to make their earlier investments profitable. In this context, higher wages can also stimulate domestic demand and balance out sources of growth, especially in surplus countries.”

Moreover, Shih’s comment above ignores copious evidence that minimum wage increases do not cause job losses. The World Economic Forum also explains that “the fact that Sweden also has a very high employment rate contradicts the argument that higher real wage growth will inevitably cost jobs.” If anything, there is still spare capacity in Taiwan’s economy at which wages can be increased further - as suggested by the high profit share.

A report titled "Minimum Wage Policy and the Resulting Effect on Employment," explains why: “Increased pay adds money to workers’ pocketbooks and allows them to buy more goods and services, creating higher demand, which in turn requires hiring more workers. The higher wage may make it easier to attract applicants and results in less turnover of workers, lowering costs of employers.”

In addition, a survey by the University of Leicester compared over 20 studies and found that, “Employers do not respond to changes in the minimum wage by reducing employment or profits, [instead] they respond by raising prices.” Even so, the author also found that, “a 10 percent […] minimum wage increase raises food prices by no more than 4 percent and overall prices by no more than 0.4 percent.”

“This is a small effect,” Sara Lemos, the author of the study, asserts.

The question therefore is not whether minimum wages should be increased – but which level they should be increased to so as to achieve real wage growth in spite of an increase in prices. If prices rise anyway in the event of increases in minimum wages, a small wage increase might only result in these higher prices negating any benefits accrued for workers. As such, bold increases to the (real) minimum wage that account for price increases, and which would give workers real benefits, should be the aim.

Basically, businesses will raise prices anyway, but they would not dare to raise them too high for fear of losing customers. So, the idea is to increase wages so that they confer real purchasing power benefits to workers.

Firms themselves also benefit from paying higher wages. The U. S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration states that, “Paying higher wages allows firms to attract workers with more and better skills [and] firms that pay their employees more are effectively able to “buy” increased morale, lower turnover, and higher productivity from employees who are committed to keeping a good job.” Not only that, David Spencer, Professor of Economics and Political Economy at the Leeds University Business School, adds: “Higher real wages would raise productivity and also induce the demand needed to absorb the extra output created by the rise in productivity.”

Allen Wallis, former Dean of the Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, puts it most succinctly when he says that, “As manpower shifts from, or avoids, low-productivity jobs where pay must be low, and moves to higher-productivity jobs where pay is higher, productivity increases for the economy as a whole.” Thereby, this “competition for the buyer’s dollar and the incentives offered in a free economy by wages, prices, and profits play a vital role in directing our efforts and stimulating efficiency, as well as in rewarding them,” Wallis concludes.

Taiwan's dilemma

Herein lies Taiwan’s conundrum – on the one hand, businesses are resistant to raising wages for fear of losing profits. On the other, it is precisely because they do not want to increase wages that their workers are not able to consume as much and thereby profits cannot be increased.

But as the ILO report shows – higher wages would lead to higher growth which will thereby benefit businesses. Look at the Nordics, for example.

The World Economic Forum maintains that: “higher real wages do not necessary threaten profits … By increasing demand and therefore sales, and boosting productivity growth, higher wages can actually help increase a company’s profit.”

In fact, there is hard evidence in Taiwan to show this: even though the minimum wage increase last year was the highest in the past 22 years when averaged out, the combined net profits of listed companies for the first nine months still went up 18 percent from a year earlier, Focus Taiwan reported the deputy head of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA)’s statistics department Wang Shu-chuan as saying. Not only that, “sales generated by Taiwan's retail sector and by the food and beverage sector both set new record highs in 2017.”

Retail sales increased by 1.2 percent from NT$4.10 trillion in 2016 to NT$4.15 trillion last year, and in the food and beverage sector, sales rose by 2.9 percent from NT$439.4 billion in 2016 to NT$452.3 billion in 2017. For both, sales in 2016 were already at record highs, and that was before the minimum wage saw its single biggest jump in two decades, suggesting that minimum wage increases do increase demand and sales, and thereby companies’ profits. So, what are we waiting for, Taiwan? Or rather, what are we waiting for, DPP?

The question then lies in whether Taiwan’s businesses and top families want to keep playing the waiting game, and to keep accumulating wealth for themselves at the expense of the workers. If so, Taiwan’s businesses have no right to blame Taiwanese consumers for not buying up their goods because this is a situation entirely of their own making – they do not want to increase wages.

As the Chinese saying goes, “五人團結一隻虎,十人團結一條龍,百人團結像泰山,” or in English, “In Unity there is strength; We can move mountains when we're united and enjoy life."

Without unity we are victims.

Perhaps then what Eklund and Desai say has the ring of truth, that “family control and ownership concentration negatively influence capital allocation [… and] display economic entrenchment and persistent misallocation of capital.” Their solution is that it is up to “key governing institutions” to reduce these “inefficiencies in the allocation of capital”.

DPP, are you listening?

Tomorrow in part 4: Social protections and saving graces

Editor: David Green