Kansas City, Powerhouse of American Architecture

Some of the country’s most interesting buildings are being created in the midwest.

Even if they wind up somewhere else, the most-interesting American buildings are constructed in Kansas City.

That’s where the A. Zahner Company, a materials lab and fabrication shop known for its inventive use of metal, is based. For most of its 118 years, the firm was a sheeting and decking company with a steady business in tin roofs. That changed in 1983, when L. William Zahner—the great-grandson of the company’s founder—met the architect Frank Gehry. At the time, Gehry was just beginning to explore erecting curvilinear designs with seemingly impossible materials. Zahner subsequently worked with Gehry to fabricate the frenetic steel-and-aluminum exterior of the Experience Music Project, in Seattle, a pathbreaking achievement for metals and architecture alike.

Today, Zahner’s client list could be mistaken for a roll call of Gehry’s rivals, among them Zaha Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Antoine Predock, Tadao Ando, Thom Mayne, and Daniel Libeskind. The company doesn’t build much “heavy structure,” as Andrew Manto, one of Zahner’s design engineers, puts it, but instead focuses on unique surfaces, such as the copper-screen exterior of San Francisco’s de Young Museum. Zahner also takes on other restoration and engineering projects; last year, Kerry “KB” Butler, the plant’s lead welder, helped perform a core analysis of the stainless-steel-clad Gateway Arch, in St. Louis, to see how it’s holding up.

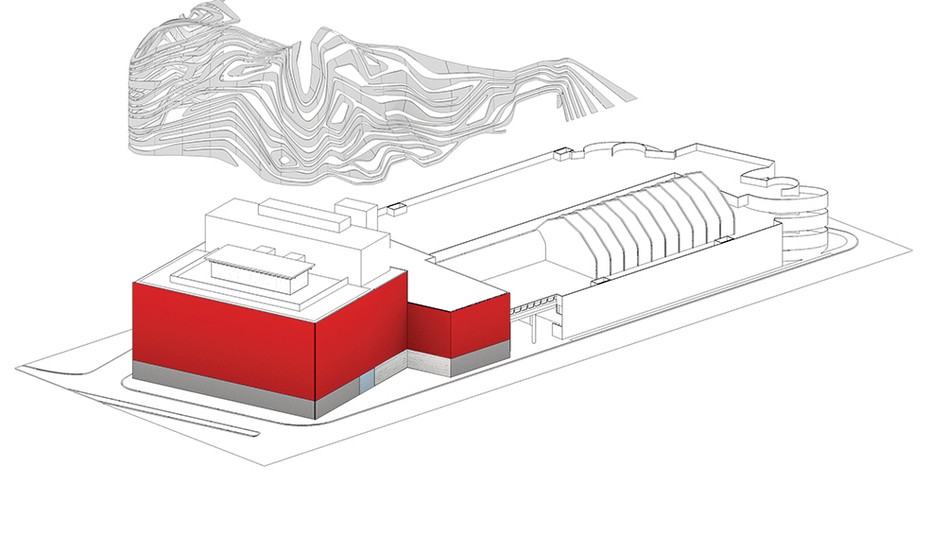

Zahner is typically working on dozens of projects at any given time, their parts in various stages of planning, manufacturing, and field-testing. Earlier this year, one of those projects was a shiny new shell for the Petersen Automotive Museum, in Los Angeles, which opened in 1994 and is scheduled to reopen in December following a $125 million renovation by the New York architecture firm Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates. If the original Petersen museum were a car, you might say that the renovation preserves the chassis while providing a new body—one designed to fit right over the original frame.

One part of the Zahner plant is essentially a tech firm, where design engineers use custom software to imagine metal surfaces and facades that in many cases have no precedent. The other part is a 50,000-square-foot metals shop, where technicians use machines to cut, punch, fold, and patinate metals with precision. Work flows back and forth between the shop floor and the computer lab as engineers and craftspeople sort out riddles in aluminum, steel, titanium, zinc, and other exotic materials. Part of Zahner’s process involves erecting models of its creations outside, to see how they look (and function) in the real world. For the Petersen, this meant constructing a scale mock-up of the museum’s “ribbons” . Finally, Zahner’s creations are sent via semitruck or shipping container to their destination, where they will be put together .

The humming, thumping shop floor is littered with parts in various states of finish. Among the machines frequently in use are a turret punch, which can notch holes of virtually any size and shape into almost any material, and a high-pressure water jet that can zip through metal. Zahner’s central innovation, known as the Zahner Engineered Profiled Panel Systems (zepps), demonstrates how far digitally driven manufacturing has come. Picture two shapes: a cube and a Möbius strip. The cube is straightforward to build, but the latter requires custom components. The zepps process marries digital modeling with fabrication to make such pieces possible. Using this method, Zahner can build something as complex as the Petersen’s winding ribbons —no two panels of which are the same—as easily as if they were being assembled from a kit.

Out in the yard, draft models of building facades hang on multistory support stands, alongside a sample of the material used for the Experience Music Project Museum, the firm’s first digital-modeling commission. The sample’s curvature is rougher, and its brushing a little less refined, than that of the Petersen ribbons. But it is Zahner’s Model T, and so it stays. “It’s a canonical building for us,” Manto says. “It was the point we jumped from tin roofs to something much more ambitious.”