Cody Wilson, Austin’s Edgelord Prince

A new documentary and a 2016 memoir by the 3-D-printed-gun designer reveal a vision of Austin as a paranoid libertarian mecca.

Above: Cody Wilson in a still from "The New Radical," streaming on Amazon and YouTube Movies.

A new documentary and a 2016 memoir by the 3D-printed-gun designer reveal a vision of Austin as a paranoid libertarian mecca.

–

by Michael Agresta

@magresta

March 12, 2018

In 2013, 25-year-old University of Texas law student Cody Wilson traveled to Vienna, Austria, to meet with a Russian oligarch. Wilson was seeking funding to design a plastic, 3-D-printed firearm, indiscernible to metal detectors and uncontrollable by law at the point of manufacture or sale. He was also laying the groundwork for another venture, DarkWallet, which would make it easier to use Bitcoin to launder money.

Both projects were rooted in what Wilson calls “crypto-anarchism,” an ideological project that seeks to employ information technologies to decentralize power and commerce to such an extent that governments are no longer able to enforce laws, and personal liberty reigns. Immensely quotable, with a gift for extemporaneous libertarian argument, Wilson had recently become a hot interview. Wired magazine had just named him one of “The 15 Most Dangerous People in the World.”

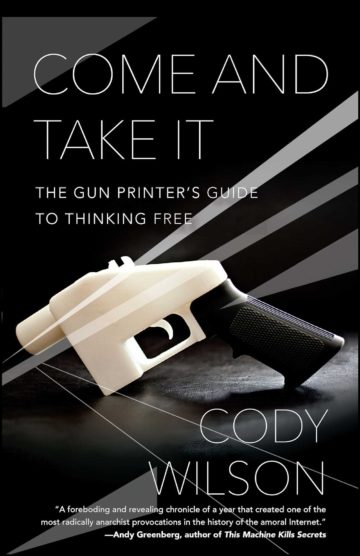

by Cody Wilson

Simon & Schuster

320 pages, $16.00

Wilson’s memoir, Come and Take It, describes the scene as Amir Taaki, his British-born partner in DarkWallet, introduces Wilson to the oligarch, identified only as “Sasha.”

“I am familiar with him,” replied the veteran of Putin-era politics, with a flat affect that made one of his henchmen smirk. “One of the most dangerous men in the world?”

The normally garrulous Wilson found himself at a loss for words. “This moment wouldn’t be the first time I’d wished the journalists at Wired understood what they were doing lobbing that title at me,” he writes. “The real Billy Badasses of the world took it as a challenge.”

Half a decade later and a year into Donald Trump’s presidency, it’s fair to conclude that Wilson’s crypto-anarchist menace was a challenge well met by the world’s true shady operators. The curious can decide for themselves with The New Radical, a feature-length documentary about Wilson and Taaki, now streaming on Amazon and YouTube Movies. Director Adam Bhala Lough paints Wilson as a prophet of a new generation of Julian Assange-emulating digital anti-statists. There’s also Come and Take It, Wilson’s memoir published in late 2016 to little fanfare.

Wilson today can feel like old news, replaced by the new-new radical of the alt-right. Even so, he continues to busk for outrageous headlines and shock-value interviews from his home in Austin — here building a crowdfunding site called Hatreon to cater to hate groups banned from Kickstarter or Patreon, there developing “ghost gun” technology to just barely comply with what federal gun laws will allow him to publish and sell. His international menace may have dimmed to mere local notoriety, but Wilson isn’t going anywhere.

“There’s a number of unemployed, over-educated young men with, you know, nothing but hate … These guys are down, man. They’re down for the struggle. They enjoy it.”

Wilson is also, as the book and film reveal, very much a product of his adopted city, and an apt symbol of Austin in the 2010s: a city of scheming entrepreneurial millennials and libertarian kooks, of rosy nostalgia for a permissive past and seething anger about encroaching big-city values, and of escalating mutual unintelligibility between blue core and red hinterland. As it turns out, the Cody Wilson story — the must-get profile that launched dozens of internationally viral videos and articles in national media — was an Austin story all along.

–

Wilson, the son of a Little Rock estate-planning lawyer, arrived in Austin in 2011 to attend law school. In the book, he describes having dabbled in leftist and anti-gun politics as an undergraduate at the University of Central Arkansas, but quickly repudiated that path.

Wilson’s descriptions of his new life in Austin emphasize isolation, by no means an unusual experience. “By night I stalked the dark ribbon of North Lamar for corners in which to work,” he writes, describing his first months in town. “All quiet but for the isolate engine and the mutterings of a derelict rocking under the hard orange watch of a streetlight.”

Much of Come and Take It sounds like this and worse. If it’s cruel to dwell on Wilson’s limitations as a writer, his own wit can be much crueler. Here’s Wilson describing a girl he dated in Little Rock the summer after his first year of law school:

My guest on those nights at the Peabody was Lauren, who, with her pale eyes, sandy-blond hair, and deliciously long legs, was much the object of my affections … Lauren worked that summer for Arkansas’s Heifer Project, an institute for mutualist agricultural lending sanctioned by all the right-minded subjects of progressive piety … Lauren enjoyed mixed-income neighborhoods, new urbanism, community gardening, and meeting for lunch at the Clinton Library. In short, she was a beautiful planner, the kind NATO sends to Eastern Europe. I enjoyed her nonlethal aid tremendously.

Wilson seems to have had trouble making friends in law school. He describes his first partner in Defense Distributed, the 3-D-printed gun start-up, as “the first person socially constructed for me entirely by Facebook” — which is to say, a stranger on the internet. During the 2011-2012 academic year, before meeting face to face, Wilson and this partner, Benjamin Denio of Arkansas, developed a plan to make a plastic gun. From their first conversation, Wilson understood it as an avenue toward fame: “[A]s soon as I had said the words, I imagined an NBC anchor delivering the nightly news…”

Quickly, his phone did start ringing: first journalists seeking interviews, then offers of partnerships-cum-friendships with a variety of Central Texans. These included brothers with a 3-D printer in Lockhart, a guy with a federal firearms license in Fredericksburg, the Longhorn Libertarians club and gun store owner Mike Cargill. Like many a bookish Southern city boy, Wilson finds romance in the company of rough men driving to the woods to shoot guns together, and much purple prose is spilt describing such excursions:

“At midmorning, we all rode into the hardscrabble together. I rocked along holding the makeshift weapon, past the desert cypress and creosote. Toward a white and flattened eminence, we went on like mechanized Janissaries …”

Wilson thrills at taking part in such adventures, but his more natural social environment is among the denizens of Austin’s Brave New Books. The conspiracy-theory bookstore did business on the Drag near the University of Texas campus from 2006 to 2017 and now operates online. “I would share some of my happiest times in Austin at Brave New Books. I’d also develop real friendships there,” Wilson writes, just sentences after summing up the place as:

“a mecca for those lunatics who draped themselves in the flags of the violent ideology of self-reliance, and who sneered out privileged and insane slogans like ‘Individual Sovereignty’ and ‘Consent of the Governed.’ Watchwords of slaver paranoiacs if there ever were.”

Brave New Books grew out of the 9/11 Truth movement, whose emissaries for a time would appear at political meetings to question the capacity of jet fuel to melt steel. The store became an unofficial hub for the Ron Paul presidential candidacy in 2008, and, though management has changed, it continues to traffic in end-times “prepping,” Kennedy assassination theories and Austrian economics.

Brave New Books also has a special relationship with Alex Jones, the Austin conspiracy-theory web and radio news magnate. Before he rose to national prominence, Jones was just another shouter on public-access TV, part of the city’s cherished oddball fabric. He purports to believe that the government puts chemicals in the water to turn men gay. He also pushes the narratives that the Sandy Hook, Las Vegas and Parkland, Florida, gun massacres were fake.

Wilson has been a guest on Jones’ show, and he cherishes the attention. In the memoir, he cops to fandom of Jones’ documentary The Obama Deception: The Mask Comes off, and in the documentary Wilson describes himself as the “finest fruits” of the conspiracy-theory community. But Jones and the Brave New Books crowd are small beans compared to the circles Wilson began to mix with as his star rose. Soon, he received invitations not just from Russian oligarchs and a Museum of Modern Art exhibition on “Design and Violence,” but also from the crypto-anarchist culture hero himself: Assange. “I was like, ‘I don’t believe in rights,’” Wilson brags onscreen after their meeting. “Assange was like, ‘I don’t believe in citizenry.’ It was this beautiful exchange.”

As Wilson ascended from lonely law-school bro to the toast of Austin’s libertarian scene to international celebrity, he began to cut a pied-piper figure in Austin. A pastier version of Tyler Durden in Fight Club, Wilson was positioned to offer work and community to other alienated young men arriving in town. As he says in the documentary,

“There’s a number of unemployed, over-educated young men with, you know, nothing but hate, who would line up to work here for $15/hr. There’s not gonna be a short supply of people who want to work here. … They get to be a part of something with some cultural caché. These guys are down, man. They’re down for the struggle. They enjoy it.”

–

While Austin has served Wilson well as an incubator for his projects, he has tended to look elsewhere for funders and partners. He shows little interest in state politics, and there’s no sign that he ever palled around with local Republican bridge-builders to the alt-right like Vincent Harris. Wilson maintains a proud distance from party politics and even the National Rifle Association, though he refers to Trump’s election as “a good thing” in The New Radical.

Wilson often invokes Ross Ulbricht, the now-jailed “Dread Pirate Roberts” (read: founder and chief executive) of erstwhile dark-web marketplace Silk Road, as a sort of fallen comrade. But in the memoir, Wilson does not indicate that he has ever actually met Ulbricht, who hails from Westlake and was living in Austin in 2011 as he built Silk Road, from which he eventually earned $80 million in commissions on sales, according to the FBI, while implicating himself in six alleged murder-for-hire agreements.

Wilson does not discuss in his memoir whether he’s received funding from Austin’s tech community (or from Sasha, for that matter). He is cagey about who funded Defense Distributed in its first year, when he threw himself into building a plastic handgun despite knowing that profiting from his design would be a crime. But halfway through Come and Take It, Wilson slips up and reveals the likely identity of his principle funder: John Walker, a retired millionaire from the early days of Silicon Valley and the co-inventor of AutoCAD. Walker now lives in the mountains of Switzerland. In the book, Wilson describes meeting his mysterious funder there. On the same date as the visit Wilson describes, Walker published a blog post about a visit from Wilson, during which Walker expresses a long-held interest in mass-distributing weaponry to populations repressed by totalitarian governments.

In interviews and in his memoir, Wilson tends to oscillate between two explanations of his motives for developing technologies that make it easier for criminals, terrorists, corrupt officials and hate groups to achieve their goals. The first explanation can be described as Wilson’s “warlord” pose. He loves to quote Nietzsche and paint himself as a barbarian king, blasting an opening for his own tyrannical instincts to thrive in an otherwise safe, dull world. He writes:

“Every political question has been answered, says the modern state. Go to sleep. Destiny is unavailable to you. ‘Revolutionary’ thought (is that the right word?) would require a passion for a real and virtuous terror. If you dare to chart a divergent course, you should also muster the awful might to initiate it.”

This warlord fantasy is, to a great extent, about women, and it shows in Wilson’s discussions of friends like Lauren, who doesn’t show up again after the book’s early chapters. At one point, he expresses what seems to be jealousy of Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s female Twitter fans.

Sometimes Wilson shifts from the warlord pose to a somewhat more appealing “true believer” pose. He has real concerns about the threat of the growing U.S. surveillance state and its extension through mass adoption of always-on telecommunications. After Trump’s election, in the film, Wilson acknowledges that an amoral, oligarch-dominated surveillance state is potentially far less pleasant to live under than an institutionally oriented, center-left surveillance state. He does not, however, grapple with the likelihood that his own efforts to ease money laundering and dark-web violence have done more to bolster the oligarchs than to undermine the surveillance of ordinary life.

So Wilson dropped out of law school to design a gun for an old libertarian with lifelong dreams of liberating totalitarian subjects by dropping pistols out of airplanes with tiny parachutes attached.

Both the warlord and the true believer poses are symbiotic parts of Wilson’s public persona. But it’s somewhat relieving to learn that Walker (and not a Sasha type) was Wilson’s principal funder, at least at the beginning. So Wilson dropped out of law school to design a gun for an old libertarian with lifelong dreams of liberating totalitarian subjects by dropping pistols out of airplanes with tiny parachutes attached. It may be misguided, but it’s also a sincerely quixotic, compellingly offbeat pursuit. In a word, it’s very Austin.

And in that sense, one might hope, his home city might offer Wilson a path back from the edge. Sure, his new alt-right friends suck, and he keeps saying embarrassing things in public, but he was eyebrows-deep in a crazy project, and we Austinites all know how tinkerers can get when they’re monomaniacally focused. Wilson even hints at it in the memoir, describing himself as being wielded by the 3-D printed gun, instead of vice versa, writing of his early journey: “I worried if I took this a few months longer, I wouldn’t recognize myself.”

On the other hand is the greater likelihood that Wilson’s exposure to media notoriety and power, and the friends he’s made along the way, have turned him into the worst version of himself: a combination of true-believer fire and warlord fury. “I’m a total zealot,” he confesses toward the end of The New Radical. “I don’t know that I was a zealot like this at the beginning. I think I was into the mischief of this, a long time ago. I liked playing with the ideas.”

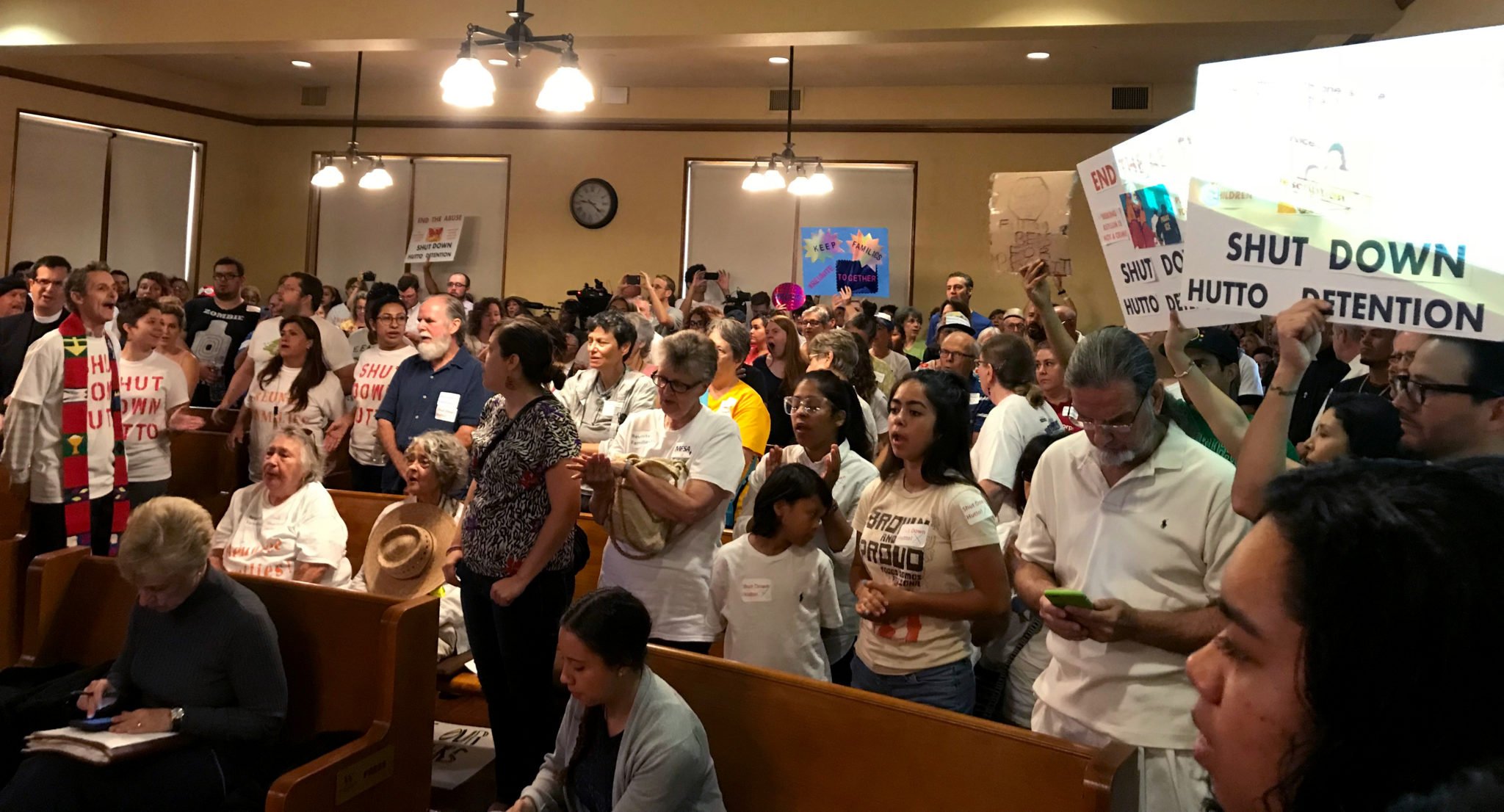

Feature photo: Cody Wilson in a still from The New Radical, now streaming on Amazon and YouTube Movies. Screenshot/YouTube