A New Generation Redefines What It Means to Be a Missionary

Traditionally, the West sent Christian missionaries to evangelize in the Global South. In 2018, should it be the other way around?

Christianity is shrinking and aging in the West, but it’s growing in the Global South, where most Christians are now located. With this demographic shift has come the beginning of another shift, in a practice some Christians from various denominations embrace as a theological requirement. There are hundreds of thousands of missionaries around the world, who believe scripture compels them to spread Christianity to others, but what’s changing is where they’re coming from, where they’re going, and why.

The model of an earlier era more typically involved Christian groups in Western countries sending people to evangelize in Africa or Asia. In the colonial era of the 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, missionaries from numerous countries in Europe, for example, traveled to countries like Congo and India and started to build religious infrastructures of churches, schools, and hospitals. And while many presented their work in humanitarian terms of educating local populations or assisting with disaster relief, in practice it often meant leading people away from their indigenous spiritual practices and facilitating colonial regimes in their takeover of land. Kenya’s first post-colonial president Jomo Kenyatta described the activities of British missionaries in his country this way: “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.”

Yet as many states achieved independence from colonial powers following World War II, the numbers of Christian missionaries kept increasing. In 1970, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, there were 240,000 foreign Christian missionaries worldwide. In 2000, that number had grown to 440,000. And by 2013, the center was discussing in a report the trend of “reverse mission, where younger churches in the Global South are sending missionaries to Europe,” even as the numbers being sent from the Global North were “declining significantly.” The report noted that nearly half of the top 20 mission-sending countries in 2010 were in the Global South, including Brazil, India, the Philippines, and Mexico.

As the center of gravity of mission work shifts, the profile of a typical Christian missionary is changing—and so is the definition of their mission work, which historically tended to center on the explicit goal of converting people to Christianity. While some denominations, particularly evangelicalism, continue to emphasize this, Christian missionaries nowadays are relatively less inclined to tell others about their faith by handing out translated Bibles, and more likely to show it through their work—often a tangible social project, for example in the context of a humanitarian crisis. Humanitarian work has long been part of the Christian mission experience, but it can now take precedence over the work of preaching; some missions do not involve proselytizing in any significant way. “It’s not to say that no one ever does any preaching—of course they do,” said Melani McAlister, a George Washington University professor who writes about missionaries, “but the notion that ‘our main goal is to convert people’ has been much less common among more liberal missionaries.” Instead, undertaking mission work can entail serving as a doctor, an aid worker, an English teacher, a farmer’s helper, or a pilot flying to another country to help a crew build wells. Many missionaries I’ve spoken to say they hope their actions, and not necessarily explicit words, will inspire others to join them.

“When I’m abroad I don’t use the word ‘missionary’ because of the stigma that it carries with other communities,” Jennifer Taylor, a 38-year-old missionary in Ukraine, told me recently. “I just usually use ‘volunteer’ or ‘English teacher’ so it actually sounds like I’m there with a purpose, and I’m not going to make you believe something you don’t want to believe.” She considers it her job to model a life with purpose, which she hopes can lead people to embrace Christianity without it having to be forced down their throat.

Beyond faith, Christian missionaries’ motivations can vary widely, in part because they come from diverse denominations. Mormons, Pentecostals, evangelicals, Baptists, and Catholics all do mission work. The work is particularly central to Mormonism, which encourages observation of the scriptural invocation to “preach the gospel to every creature.” Pentecostals and evangelicals are also among the more visible. (By way of comparison, at the beginning of this year, 67,000 Mormons from around the world were serving as missionaries, while the U.S.-based Southern Baptist Convention reported having sent only about 3,500 missionaries overseas.) They may be driven by their faith, the wish to do good in the world, and an interest in serving a higher purpose. But their motivations, according to young Christian missionaries I’ve spoken to, also include everything from the desire to travel abroad to the desire for social capital. Often, these are mutually reinforcing.

Faith, of course, remains a primary driver. Many feel that they’ve been “called,” that they’ve received “a transcendent summons,” said Lynette Bikos, a psychologist who has researched children in international missionary families. For some, the sense of a calling might lead to joining the Peace Corps or a non-profit, but “what distinguishes missionaries is this sense of transcendent missions; they’re doing it for religious purposes—to dig wells, but to do it in a Christian context,” Bikos said.

Among the new generation of Western Christian missionaries, the so-called “white savior complex”—a term for the mentality of relatively rich Westerners who set off to “save” people of color in poorer countries but sometimes do more harm than good—is slowly fading. “I think for many missionaries today, contrary to when I was growing up, missionary experience is primarily seen through the lens of social justice and advocacy, with proselytizing as a secondary condition,” said Mike McHargue, an author and podcaster who writes about science and faith. “I think young Christians today have experienced and internalized some critique of that colonial approach to mission work.”

Sarah Walton, a 21-year-old Mormon from Utah, went on a 19-month mission trip to Siberia when she was 19; she said her desire to go emerged from her belief in God. “I was really lucky to have the experience to go outside the United States,” she told me. “Since then I’ve become addicted to traveling and going outside the U.S.” She’s studying in Israel this year.

If travel offers young missionaries a chance to taste life overseas, it also offers the tantalizing opportunity to see their work have a strong humanitarian impact or deliver quantifiable religious results, like a number of baptisms. In some cases, young missionaries reap a kind of social capital for the apparent strength of their faith relative to their peers. Taylor, who describes herself as non-denominational, was 18 when she decided she wanted to be a missionary. At first, her friends thought it was a phase. “A lot of them have ‘normal’ jobs,” she explained. But “most of them are actually supportive whether they’re believers or not. … They still think what I’m doing is very impressive.”

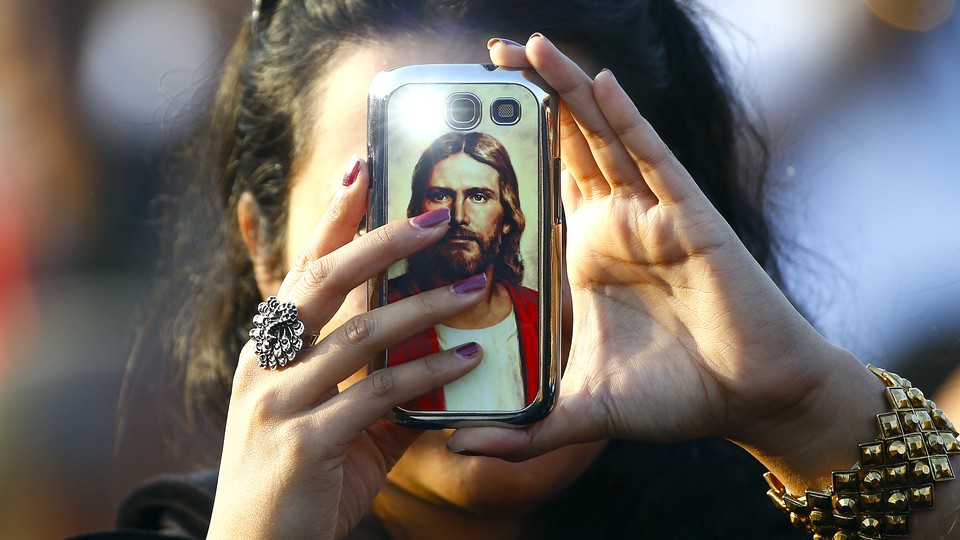

Young missionaries today also have the advantage of being able to find community online. On Instagram, the #missionarylife hashtag is dominated by photos of young people setting off on their trips and, once they’ve arrived, posing with camels or lions. These posts earn them virtual cachet in the form of “likes,” but they also offer a space to talk about their experience.

On Christian forums and blogs, people ask probing questions, discuss experiences, and question whether their faith is strong enough to preach to others. Jeremy Goff, 26, is a Mormon who blogs about his lifestyle and faith. Originally from Colorado, Goff worked for two years at a Jamba Juice to make enough money to fund his mission trip. He stayed in the United States to do his work. After serving as a missionary in Maine, he went back to work to save up money for college. Now a sophomore at Utah Valley University, he talks to other young missionaries online about preparing for the challenges of the mission experience.

Meanwhile, missionary life looks very different for people coming from outside the West. “To a surprising degree, third-world Christians, or ‘majority-world’ Christians in the language of political correctness, are not burdened by a Western guilt complex, and so they have embraced the vocation of mission as a concomitant of the gospel they have embraced: The faith they received they must in turn share,” said Lamin Sanneh, a professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School. “Their context is radically different from that of cradle Christians in the West. Christianity came to them while they had other equally plausible religious options. Choice rather than force defined their adoption of Christianity; often discrimination and persecution accompanied and followed that choice.”

At the Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary in Amman, for example, two-thirds of the 150-odd student body comes from within the Middle East, according to the founder Imad Shehadeh. The curriculum focuses on understanding Arab culture, the role of Arab Christians, and how to minister in the region. The majority of the students are setting out to be church leaders, build new churches, and proselytize; students are asked to serve in Arab countries. “We had a couple go back to Aleppo” in Syria, Shehadeh said. “They’d lost everything, came here, studied here. They did so well. They returned to Aleppo—they’re leading a church there. They said, ‘We cannot go back to our countries when things are okay. We need to go back when things are tough.’”

Mission work in times of crisis can pair well with religious revivalism, Sanneh said: “Almost everywhere, the return of religion has occurred in the midst of social crisis and political upheaval—there is more than a superficial connection here. Economic goods alone do not exhaust the human desire for consolation. That truth has challenged Christian missionaries to serve in humanitarian work, in education, health care, peacemaking, and reconciliation.”

While mission work may have evolved in some countries and denominational groups, several organizations still offer trips to countries where proselytizing can be ethically dubious, applying religious pressure to vulnerable groups. Some organizations directly target refugees for conversion. Operation Mobilization offers trips to Greece, noting, “The Lord has given us a wonderful opportunity to witness to displaced people from the Middle East, many of whom would have never had the opportunity to hear the Gospel in their home countries.” ABWE offers chances to work with the persecuted Burmese Rohingya population that has sought refuge in Bangladesh, noting that “God is using this crisis to bring this people to those who can minister to both their physical and spiritual needs. … Providentially, this has come on the heels of the completion of the Chittagonian Bible translation—the language of the Rohingya.”

In Jordan, Father Rif’at Bader, the director of the Catholic Center for Studies and Media, said that missionaries can harm the image of existing Christian communities. “When the Syrian refugees came to Zaatari camp, many missionaries or evangelizers came to the camp and they were speaking frankly: ‘You want to regain your peace? Join Jesus Christ.’ These are vulnerable people. Some were trying to attract them [by offering] visas or money to change their religion.”

In some places, accusing people of performing missionary work is a way to target Christian communities. In India, for instance, Hindu right-wing activists have accused Christians of being missionaries or attempting conversions, using this as a pretext to attack Christians.

And missionaries themselves face danger in some countries. Last year, for instance, two Chinese 20-somethings reportedly working as missionaries in Pakistan were kidnapped and killed in an attack claimed by ISIS. In other cases, missionaries confront political and cultural barriers. During Walton’s mission to Siberia, Russia barred proselytizing. She and her group shifted their focus to working with local church members instead. “When you think about missionary work, you mostly think of how to convert people to your faith, but a lot of the things I did as a missionary were to help people who were already of our faith to be stronger and understand better,” she said. “We took a lot of precautions when the law was passed—we weren’t supposed to talk to people on the streets at all. We were very cautious, but I wasn’t ever scared.”

In the end, people choose the work over other options because they feel it gets at something fundamental. “Someone said to me, ‘You could work on a cruise ship,’” Taylor recalled. “But there’s something about working with kids who don’t have families, who don’t know the value of their lives, and treating them as human beings.”